The more you know about bamboo, the more fascinating the plant becomes. From the strength of its fibers to the tenacity of its roots to the unpredictability of its flowering, this is a grass like no other. At the same time, from an anatomical and botanical perspective, it is a grass like any other.

Fundamentally, the anatomy of bamboo is perfectly characteristic of a grass. When you look at a giant bamboo specimen, towering 50 or 60 feet high, with lumber-like poles strong enough to build a house, it’s hard to believe it’s a grass. But if you understand the anatomy of grass, you’ll recognize that bamboo absolutely belongs to the same family, Poaceae. Moreover, knowing the bamboo anatomy and terminology will enable you to discuss the plants with greater clarity and fewer misunderstandings.

In the following article, we will cover nine key components of the bamboo anatomy. We’ll also clarify a few other terms having to do with the growth and behavior of bamboo. Ultimately, this will better enable you to identify what kind of bamboo you are looking at, and how you can expect it to grow and spread. It will also help you speak more precisely about bamboo, in case you have a question or concern that you’d like to discuss with a bamboo expert.

Finally, it should make it easier for you to explain your bamboo garden to your friends, especially to your neighbors, who might be terrified to see bamboo growing so close to their property line. With greater confidence and expertise, you can explain to them the difference, for example, between a running bamboo and a clumping bamboo. And you can quell their fears of an invasive grass that might wreak havoc on their flower beds and sprinkler lines.

NOTE: This article first appeared in September 2020, most recently updated in October 2023. Special thanks go to Natalia Reategui for her technical advice and assiduous attention to detail.

Basic parts of the bamboo anatomy and morphology

Rather than listing them in alphabetical order like a glossary, we’ll look at these terms conceptually, in order of importance. In other words, we’ll study the parts of the bamboo anatomy in roughly the order that the plant produces them, from the ground up.

1. Rhizomes

This is where the magic happens. The rhizomes are like the heart, the brain and the legs of a bamboo plant, all rolled into one. So long as the rhizomes survive, the bamboo will survive. You can think of the rhizome as the root of the plant, but it’s something far stronger and more robust than a simple root. Some other plants that grow from rhizomes include ginger, turmeric, irises and certain kinds of orchids.

(If you really want to geek out, check out our fascinating article on the etymology of the word rhizome.)

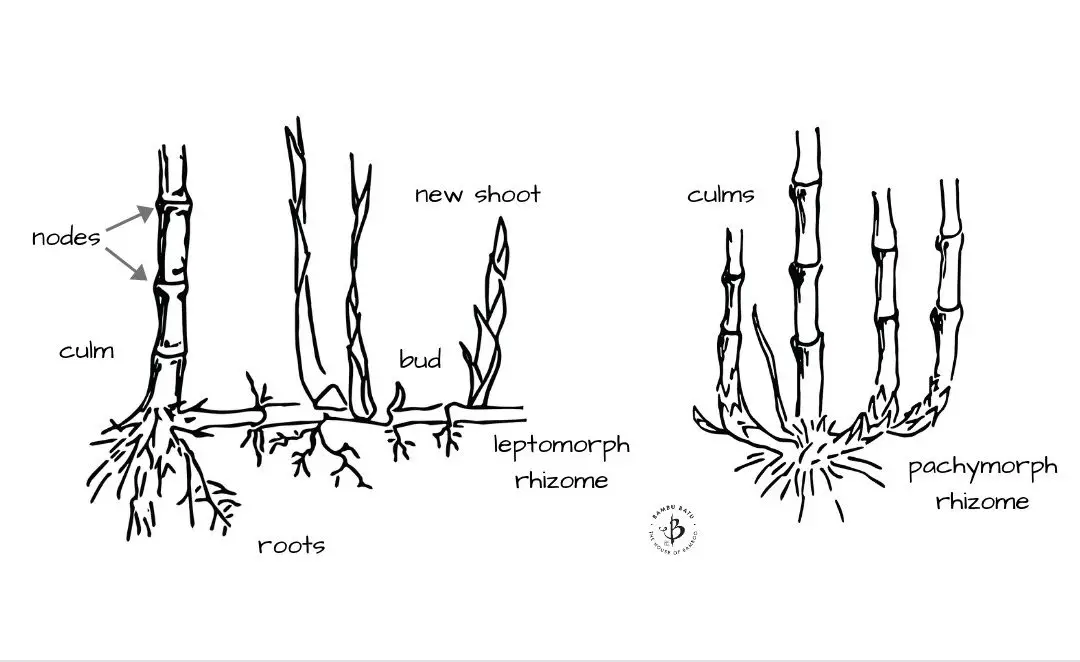

There are essentially two different types of rhizomes, and this is the first way in which we can classify bamboo. There are nearly 100 genera of bamboo, and more than 1,500 species, but we start by separating them into runners and clumpers.

Running bamboo has what are called leptomorph or monopodial rhizomes, which grow horizontally away from the main plant, causing tit to spread out, sometimes quite aggressively.

- Monopodial, in botany, means it grows out in a single point. Usually this refers to a part of the plant growing upward, but in the case of a monopodial rhizome, they grow outward. Also, the bamboo will produce a network or rhizomes, where each one grows out towards a point. Most bamboo is also monocarpic, meaning that it will only flower once its lifetime before it dies. And to make it even more confusing, bamboo often tends to be monotypic. That means it grows in the wild in groves or colonies made up of just one species, as opposed to a mixed forest consisting of ferns, shrubs, evergreens, etc. But there’s no connection between bamboo being monopodial, monocarpic and monotypic.

- Leptomorph is another word to describe the rhizomes of a running bamboo. The word means “thin”, but sounds like “leap”, which may help you remember it. Consider the old saying about bamboo: “The first year it sleeps, the second year it creeps, the third year it leaps.” This fairly well describes the growth habit of running bamboo, which appears pretty innocuous in the first couple years, and then suddenly sprouts up everywhere.

Clumping bamboo has what we call pachymorph or sympodial rhizomes. For the most part, these rhizomes stay pretty close together, and most clumping bamboos will stop spreading once they reach a certain size.

- Sympodial rhizomes split off more, rather than running out in a straight line. The result is a lot of u-shaped offshoots, growing upward, but keeping close together, in a clump.

- Pachymorph is the other term for clumping bamboo rhizomes. It sounds like “pack”, which makes it easy to remember, but actually it means “thick”. It’s the same prefix in the name pachyderm, the family of “thick-skinned” animals which includes elephants and rhinoceroses.

2. Roots

Often, when people talk about bamboo roots, what they really mean are the rhizomes. We even refer to them as the rhizome roots. But technically, the roots are something slightly different from the rhizomes.

Like the roots of other non-rhizomatous plants, these are the soft, white, fibrous tendrils that creep down into the dirt. In bamboo, the roots tend to emerge from the nodes of the rhizomes. While the rhizomes spread out and generate the growths that will become new shoots and culms, the delicate roots mainly grow downward and are responsible for drawing water and precious nutrients out of the soil.

3. Buds

Unlike the buds of a plant that grow into flowers, bamboo rhizomes produce buds that will eventually break through the soil and grow into shoots. When they are just brand-new growths, and have yet to reach the surface, we still call them buds.

Buds also appear at the nodes of culms and branches. If left alone, the buds will grow into branches. But if you’re clever, you can propagate new plants from these buds through a technique known as aerial layering.

4. Shoots

Once the bud breaks out and sees the light of day, it becomes a shoot. Shoots have a point on the end, with a shape that resembles a spear or a sharpened pencil. Sometimes they are about the same size as a pencil, but with a giant timber bamboo, the shoot can be as thick as your thigh and as tall as you.

Still soft and tender, the fresh shoots of many bamboo species are edible, and often quite tasty. They are best harvested about two weeks after they appear, and should be cut as close to the rhizome as you can get. But before you dig in, know that it can be dangerous to eat the shoots raw. For the vast majority of species, the shoots must be boiled or fermented in order to remove the toxins before you can eat them.

5. Culm sheath

As the shoots come up, you’ll notice that they are wrapped in a paper-like sleeve. Culm sheaths from larger bamboo can be used for different sorts of arts and crafts. Often you see a white powdery substance on the culm sheath. Because of this powder, the sheaths should not be used for any culinary applications. If you’re looking for something to wrap food in, try the giant leaves of Indocalamus tessellatus instead.

Botanists long considered the culm sheath to be a kind of modified leaf. But new research suggests that a culm sheath, based on anatomical structure and how it attaches to the node, is more similar to a specialized branch.

When it comes to identifying bamboo species, the culm sheath shape is one of the most important markers. Only careful examination of the flowers (which very rarely emerge) can provide a more reliable key. The top of the culm sheath has something called a culm blade, which is separated from the rest of the culm leaf by a thin line called the ligule. The length of the ligule and the shape of the culm blade will vary considerably between species. And unlike other characteristics, such as culm color, leaf size, or even the presence of thorns, this culm sheath shape will not be affected by environmental conditions.

6. Culm

We like to call them canes, poles or stems, but the anatomical term for the main stalk of any grass, including bamboo, is a culm. The culms are almost always round (cylindrical), but Square bamboo, Chimonobambusa quadrangularis, has unusually square culms.

As the sheaths peel off and drop, the shoot graduates into a culm. This usually takes several weeks to a few months, depending on the species and the climate. By this time, the shoot or culm has reached its full height. Once the growing season is over, the culm won’t get any taller, although it will continue to grow some branches, which could add to the overall height of the plant.

7. Node

The distinctive joints along the culms of bamboo are called nodes, or nodal joints. In some cases, the nodes can be very knobby and obtrusive. Other bamboo plants have nodes that are very smooth. But you’ll always see a ring around the culm to identify the node. Bamboo culms are generally hollow, but at the nodes they are solid.

This is a typical characteristic of all grasses. Branches grow out at or slightly above the nodes, usually on alternating sides of the bamboo culm. You will notice that the rhizomes have nodes as well. Soft, white roots appear on the nodes of the rhizomes.

Close examination of the nodal joint can often be very helpful when it comes to recognizing a bamboo species. Members of the genus Phyllostachys will characteristically have two main branches and a few smaller ones at each node. Bamboo belonging to Bambusa or Dendrocalamus will have one major branch and several smaller ones.

In the photo above, we can see Bambusa balcooa with a distinctive supernodal ridge, faint but easily detectable with a sensitive finger. The branches are emerging just above the sheath scar and right below the supernodal ridge.

8. Internode

The spaces in between the nodes, where the bamboo is smooth and hollow, are the internodes. Some bamboo species have longer internodes than others. The amount of water and direct sunlight a plant gets can also affect the length of the internodes. Some varieties of bamboo have differently shaped internodes, like those that bulge out conspicuously in the case of Buddha’s Belly.

Typically, the internodes are hollow, with an empty space inside called the internodal cavity, whereas the bamboo is solid at the nodes. However, there are a number of bamboo species which have culms that are solid all the way through.

9. Sulcus groove

A subtle but important feature, the sulcus groove is a shallow indentation that runs along the internodes, on alternating sides, on certain varieties of bamboo. It is important because it allows you to identify the bamboo as a member of the genus Phyllostachys. And if you know that it’s a Phyllostachys, then you also know that it’s a running bamboo. However, if you don’t see a sulcus groove, that doesn’t prove that it’s a clumping bamboo.

UPDATE: It has recently come to my attention that certain members of the genus Chusquea, neotropical clumping bamboo, are also known to exhibit a sulcus groove. So this is not an entirely reliable method to identify Phyllostachys or running bamboo. But these two genera are quite different in many other respects, making them difficult to confuse with one another.

Bamboo Flowers

One of the most important and also perplexing parts of the bamboo plant are the flowers. When you want to identify a bamboo species, the flowers are probably the most important feature to study. In general, it is the morphology of a flower that is used to classify plants and trees and to observe which plants are most closely related.

To learn all about this botanical conundrum, please refer to our article on Bamboo Flowering.

Further reading

If you enjoyed this article about bamboo anatomy and morphology, please consider sharing the blog post or subscribing to our mailing list. You might also be interested in some of the following links:

Bamboo Anatomy good information.

Your information is really a PowerPoint message to improve upon my research. Thanks Bambubatu 👍👍

Wow, I would have thought that information here is unprofessional, but it’s actually helpful and accurate! I am currently doing a project on bamboo taxonomy and evolution, and your website is one of the few faced toward the public able to explain technical and up-to-date information so easily understood! It is very helpful, thank you

Thank you, Jagger! I’m quite determined to provide reliable information – through all my blog posts, youtube videos and in-person workshops!

Dear Bambu Batu, I enjoy reading your articles. Thanks. It’s said that bamboo shoots give a cracking sound during their rapid growth stage possibly by rubbing or popping the sheaths. Any insights? Cheers.

Thanks Max. Yes, I believe that’s correct, but I’ve never heard it for myself.