When people talk about bamboo, they often speak in hyperbole, describing the plant’s astronomical growth rate and its mind-boggling variety of uses. In fact, there are some 1,500 different species and cultivars of bamboo with an enormous range of qualities and characteristics. Some are thin, wispy and ornamental, while others may be massive, thorny and industrial. But Moso Bamboo, also known as Phyllostachys edulis, is one species of bamboo worth raving about.

Phyllostachys edulis, better known as Moso Bamboo, is a prevalent species of timber bamboo, native to China and Taiwan. Widely used in the production of flooring, textiles and building materials, Moso is arguably the most economically important bamboo species in the world. In ideal conditions, this giant grass can grow three feet a day and reach 100 feet tall. The scientific name, Phyllostachys edulis, means something like ‘edible bamboo’. But until recently it had been listed as Phyllostachys pubescens, meaning ‘hairy bamboo’. The common name, Moso, comes from the Chinese mao zhu, which also means hairy bamboo.

Moso is nothing new, but in recent years it has sparked a revolution in agriculture, textiles and construction. When you hear about bamboo clothing and bamboo flooring, these are products of Moso. When you see bamboo scaffolding on skyscrapers in Hong Kong and China, it’s very likely Moso. And when people speak of bamboo growing two or three feet a day, Moso is one of the varieties that can actually do that. (See our article on Giant Bamboo to learn more.)

This article — first published in June 2019 and last updated in September 2024 — is part of an ongoing series about selected bamboo species. Take a look at some of these other pages to learn more.

- Directory of Bamboo Species

- Bambusa balcooa for better biomass

- Black bamboo

- Borinda fungosa: Chocolate bamboo

- Chimonobambusa quadrangularis: Square bamboo

- Dendrocalamus asper: Giant bamboo

- Golden bamboo

- Hiroshima bamboo

- Semiarundinaria fastuosa: Temple bamboo

Characteristics of Moso Bamboo

Native to Southern China and Taiwan, Phyllostachys edulis thrives in the warmer, balmy climates. In these regions, the plant can reach its full potential, with towering culms of 90 feet or more, and growing a couple of feet a day in the growing season. But like most Phyllostachys, it can also tolerate more temperate zones and is cold-hardy down to about 10º F.

Members of the genus Phyllostachys are running bamboos, meaning that they spread and propagate by way of sprawling rhizome roots. From this complex underground root system, new culms shoot out of the ground in the growing season and quickly grow to their full height. A mature grove of Moso Bamboo will put out shoots with a 4-5 inch diameter.

Moso looks very similar to other large species of Phyllostachys, including Vivax, Giant Gray (Ph. nigra ‘Henon’), and Japanese Timber (Ph. bambusoides). In fact, even experts can have a hard time telling them apart. Moso’s older species name, pubescens, meaning hairy, refers to the fine hairs that grow on the young culms. This is one way of distinguishing it from its close relatives.

Moso bamboo is especially revered for its great size, impressive growth rate, and tremendous usefulness. In parts of China, where it is native, this species flourishes in vast forests.

Check out our in-depth articles on Timber Bamboo and Running Bamboo to learn more.

Cultivating Moso Bamboo

In the right climate, this can be a very impressive and rewarding species to grow, either ornamentally or commercially. The vast majority of Moso grows in forests and plantations in China. Over the last few decades, they have established about 3 million hectares of Moso. More than half of this bamboo occurs in natural forests, but it is managed by private interests, to be used for a wide range of applications. It represents a $36 billion-a-year industry in China.

Attempts to cultivate Moso in the Unites States have proven challenging. The best results have been in the Southeastern states, north of Florida. The most successful plants have come from tissue propagation. Even so, the small saplings are slow to establish. West of the Mississippi, Moso is especially difficult to grow. (See below.)

Once every 75 years or so, a Moso Bamboo plant will flower and produce seeds. In some varieties of bamboo, every member of a given species will flower at the same anywhere in the world. This phenomenon, known as synchronous blooming or gregarious blooming, does not occur with Moso. Instead, it exhibits sporadic flowering. Even so, if the plants are propagated from tissue culture, then they are genetically identical, and that means they will flower at the same time. Such a flowering event could be catastrophic for the farmer who doesn’t maintain a diverse crop.

In many varieties of bamboo, the plant will die after it flowers and goes to seed. This is called monocarpic. This is NOT the case with Moso. Although the vegetative growth will be inhibited for a couple of years while the plants put their energy into flowering.

A healthy stand of Moso can produce thousands of seeds and most of them will germinate, while the mother plant survives. Rats and rodents, however, will generally eat a significant portion of these tender seedlings, which tend to be only 2 mm in diameter. You can also purchase bamboo seeds on the internet, but in most cases, the seeds are not reliably identified. Often, they are not the right species, or not bamboo at all.

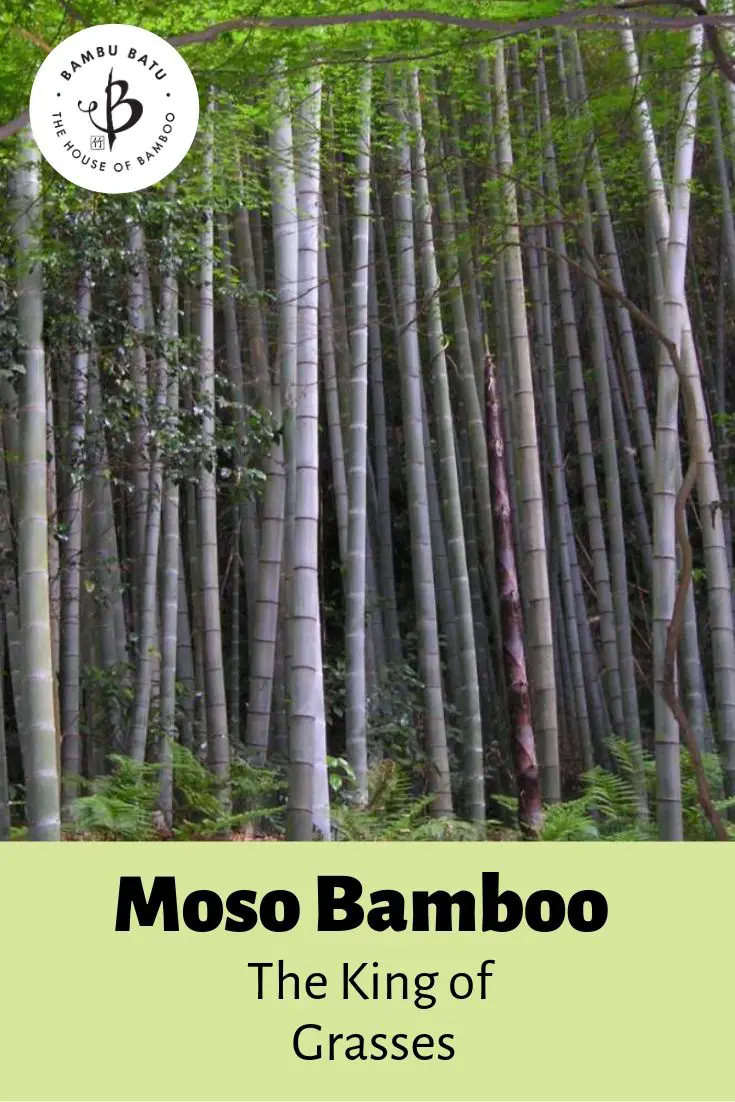

Moso Bamboo at Arashiyama, Japan

There are few things in nature that can rival the experience of walking through a giant grove of Moso bamboo. If you’d like to visit such a forest, the Arashiyama Bamboo Grove in Kyoto, Japan, is perhaps the most impressive. It covers about 6 square miles.

A popular tourist destination, Arashiyama is probably also the most frequently photographed bamboo forest on earth. If you Google “bamboo forest”, you are certain to see some famous images of this majestic Moso grove.

Can I cultivate and farm Moso Bamboo in the U.S.?

As the world’s most famous bamboo species, there’s international interest in growing this impressive specimen. But the preponderance of commercial Moso farming takes place in China, where the species is indigenous. It’s much happier in that native climate. Within the U.S., the Deep South has the best growing conditions for Moso Bamboo. Even so, many growers describe it as a finicky species that is difficult to propagate and slow to get established. Many prefer to grow Giant Gray bamboo instead, also called Phyllostachys nigra ‘Henon‘, or just Henon for short.

It seems to do best in places like Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. A company called Only Moso launched a commercial bamboo business in Gainesville. Florida, in 2011. But Florida turns out to be a little too warm and tropical for this species. Only Moso now grows mostly Asper bamboo. (See below.)

Some farmers grow Moso ornamentally in Oregon and the Pacific Northwest, where it can survive but does not thrive. Without the hot summers and humidity, it will not reach its maximum height and girth. Moso is better suited for growing east of the Mississippi River, and south of the Mason-Dixon line. But most American farmers still prefer Henon.

West of the Mississippi and in USDA zones 7 and 8, Phyllostachys bambusoides, aka Japanese Timber Bamboo or ‘Madake’, a closely related timber variety, grows especially well. It is slower to spread, but culms can get even larger than those of Moso, and are excellent as a building material.

Have a look at our article on Bamboo Farming in the US.

Phyllostachys edulis ‘Heterocycla’: Tortoise Shell Bamboo

The subspecies ‘Heterocycla’ isn’t nearly as important economically, due to the odd and irregular shape of its culms. But this unusual pattern makes for a beautiful specimen plant and a dazzling addition to any bamboo enthusiast’s garden. In Japanese, they refer to this variety as ‘Kikko’, which literally means ‘tortoise shell’. The cultivar doesn’t grow nearly as tall as the original species, and it lacks the industrial applications, but it is a very desirable plant among bamboo collectors.

The Many Uses of Moso

The magnificent size and vigorous growth habit of Moso Bamboo make it the perfect candidate for a wide range of practical and industrial applications. Moso from China has become especially important for the production of bamboo flooring and bamboo clothing.

Bamboo Flooring

Bamboo flooring took the building industry by storm about 20 years ago, quickly becoming available from hardware stores and flooring specialists everywhere. Unlike traditional hardwoods, bamboo reaches maturity within 4-5 years, while the trees could take 20-100 years to mature. Bamboo, with its high metabolism, can also sequester about 50% more carbon than a typical forest.

In addition to the ecological benefits of bamboo, Moso also produces a very hard wood, making it an ideal material for things like flooring and cutting boards. According to ProSand Flooring, standard bamboo flooring has a Janka hardness rating of around 1380. This is comparable to most oak varieties, rated around 1300 to 1400. More innovative types of bamboo flooring, using a strand woven technique, have scored from 3000 all the way up to 5000.

Besides flooring, engineered bamboo lumber offers a fabulously renewable alternative for cabinetry, construction, and solid bamboo furniture. A number of companies, like PlyBoo and Dasso, are using Moso bamboo for housing and other building applications.

As much as we like to advocate the use of bamboo as the environmental silver bullet, it is important to be aware of certain ecological concerns. As a laminated wood, bamboo flooring does require a urea-formaldehyde (UF) adhesive to bond together. These adhesives can off-gas and pose other environmental problems. Still, bamboo uses far less formaldehyde than other materials like particle board. And formaldehyde-free bamboo is also available now.

Another issue, when bamboo flooring exploded in popularity, was the removal of native forests in China for the purpose of cultivating commercial bamboo. This sort of deforestation has led to the destruction of natural wildlife habitats and soil erosion, and could easily outweigh any environmental benefits of bamboo. It’s important, therefore, to learn as much as you can about your bamboo supplier, and see that they meet all the highest standards of certification.

Learn more about FSC certified bamboo and lumber.

Bamboo Clothing

Remarkably hard, on one hand, bamboo can also produce a rayon fabric that is incredibly soft, on the other. Shortly after the appearance of bamboo flooring, we began seeing socks, t-shirts, and towels made from bamboo.

Along with the well-reported ecological benefits of bamboo—fast-growing and readily renewable without the need for pesticides and herbicides—bamboo fabric also boasts a number of advantages in performance. Most obvious is bamboo’s softness. Like cotton or any other conventional textile, bamboo can be woven into any kind of fabric. But the result is always uniquely soft, with an uncommon mix of cool silkiness and warm fuzziness.

Additionally, bamboo material is naturally anti-microbial, hypo-allergenic, odor-resistant and temperature-regulating. It may sound too good to be true, but the properties of bamboo are plainly evident if you sleep on a set of bamboo sheets or wear a pair of bamboo socks two days in a row. We’ve also heard from many customers with sensitive skin disorders and serious allergy issues that bamboo is one of the only materials they can wear.

Bamboo’s very high absorbency also makes for some exceptionally nice towels. But be advised, bamboo socks and t-shirts will take a bit longer to dry for this same reason. Generally, this is not a problem. If you’re keeping your carbon footprint down and using a drying rack instead of an electric dryer, just leave the clothes on the rack a little longer. If you’re traveling, however, and trying to dry your clothes on a line in your hotel room overnight, bamboo might not be your best choice.

Processing bamboo for textiles

Some have expressed concern over the pulping process that goes into making viscose fabric from bamboo. In fact, caustic soda (or lye) is used to extrude the cellulose from the stalks and leaves of the bamboo before it can be spun into thread and woven into fabric.

The primary concern here is how the manufacturer disposes of this byproduct after pulping. It is possible to reuse and recycle the lye, and certain manufacturers are bound to be more conscientious than others. We have always been committed to working with the most ecologically responsible producers as possible.

Most of us who work in the bamboo industry are determined to see it being used in the most ecological way possible. It’s good to know that many have been improving the standards of cultivating and processing bamboo over the years.

Cotton, by comparison, is extremely pesticide-intensive to grow, as it is very vulnerable to insects and other pests. It also requires a great amount of irrigation, because it is typically cultivated in hot, dry climates. And even organic cotton must go through a processing stage before it’s spun and woven into fabric.

Phyllostachys edulis is edible

Finally, we need to talk about how Phyllostachys edulis got its name. Long before the advent of bamboo floors and bamboo underwear, Chinese foodies were making use of Moso Bamboo’s tender young shoots.

So Moso earned its botanical name from this characteristic. Actually, many varieties of bamboo have fresh culms that are edible. This species just happens to be one of the most majestic, widespread and recognizable in China. Not only that, but given the plant’s size, you can practically make a whole meal out of one shoot!

Take a look at our article on Edible Bamboo Shoots to learn more.

Other superior species

If you’re looking for other varieties of bamboo that are especially useful and fast-growing, Guadua angustifolia is one to watch out for. Native to Central and South America, Guadua is a clumping genus of mostly timber bamboos. They make an excellent building material, and have been used widely throughout the continent to create some very impressive structures.

Guadua grows best in equatorial regions like Colombia and Ecuador and is seldom cultivated outside of Latin America. The fresh shoots of this species are not considered edible.

Tropical (clumping) bamboo generally has thicker culms and is superior to temperate (running) bamboo for building and construction. In South America, they claim that Guadua is the strongest bamboo on earth. But in Indonesia, they make the same claim about Dendrocalamus asper.

Asper, like Moso and Guadua, can grow close to 100 feet tall and with culms 5 or 6 inches in diameter. Since the 2010s, farmers throughout the world (the tropical world, at least) have taken to cultivating Asper for industrial use. Native to Indonesia and Southeast Asia, this giant species now grows on farms in Africa, South America, and Florida. The shoots of Asper are also edible, providing an additional value for farmers.

For more details, have a look at our in-depth article on The best bamboo for building and construction.

Further Reading

To learn more about the ecology and versatility of Moso and other species of bamboo, check out some of our other articles.

- What’s so great about bamboo?

- 10 Best varieties of Bamboo for your garden

- Best bamboo for poles

- Hemp vs. Bamboo: The ultimate comparison

FEATURE IMAGE: Phyllostachys edulis, or Moso bamboo, flourishes at the Bambu Parque in Portugal. Photo by Fred Hornaday.

I am interested in investing in bamboo growth and manufacturers who use it. Are there any companies on the stock exchange doing well?

That’s great to hear, Carole. But at this time, even the biggest bamboo companies (Bamcore, Lamboo, Only Moso, and Rizome in the US, or Bamboo Logic in Europe) are privately held. Not on the stock market.

I live in the north of Argentina (Salta). I have planted a few moso bamboo in a field in 2017. I’m very happy, bamboo is my life.

I would love to start a bamboo farm. I live in north eastern Kentucky. Would this be possible?

It definitely possible. But Moso is probably not the best choice. Consider some of these Bamboo Species for Farming.

II picked up about 30 feet of healthy Moso Bamboo rhizome. Its not all one piece. Its in several pieces, each at least 1 foot long.

Is it possible to successfully plant them. I am in Columbia South Carolina. The rhizomes are from a healthy grove.

If it is possible to successfully plant them, I appreciate any info you can provide.

Thanks in advance for any information you may provide.

Freddie Watson 803-467-0458

Moso is a particularly difficult species to propagate. But generally, rhizomes are one of the best ways to go. Moso enjoys the company of other bamboo plants, so try placing some of the rhizomes near an existing grove, including other varieties of Phyllostachys.

I loved this post on Moso bamboo! It’s fascinating to learn about its versatility and strength. I’m particularly interested in how it can be used in sustainable building practices. Looking forward to trying out some bamboo products!