Bamboo is something of a symbol of Far Eastern culture. So it’s not unusual for our love of bamboo to spill over into other Asian ideas and aesthetics, like bonsai, meditation and Wabi-Sabi. But today we’re going to explore and unpack another treasure trove of Eastern symbolism, the mighty Ganesha.

Some call him the elephant head, some call him the Remover of Obstacles. What is this fascination we have with the glorious Lord Ganesha, or Ganesh, India’s mighty and most revered elephant deity? None can deny the charm of the thick-skinned behemoth, the largest animal to walk on land since the ice age, with its chunky tree trunk legs, its floppy ears and that ridiculous protrusion of a trunk. Surely this is a creature steeped in symbols and meaning.

Legend of both the savanna and the big top, the elephant lends itself easily to fairy tales and folklore. But take a close look at the iconography of Ganesha and you’ve got a regular circus of mythological exegesis.

Note: This article first appeared in November 2015 and was most recently updated in March 2025.

Lord Ganesha: Elephant god of wisdom and success

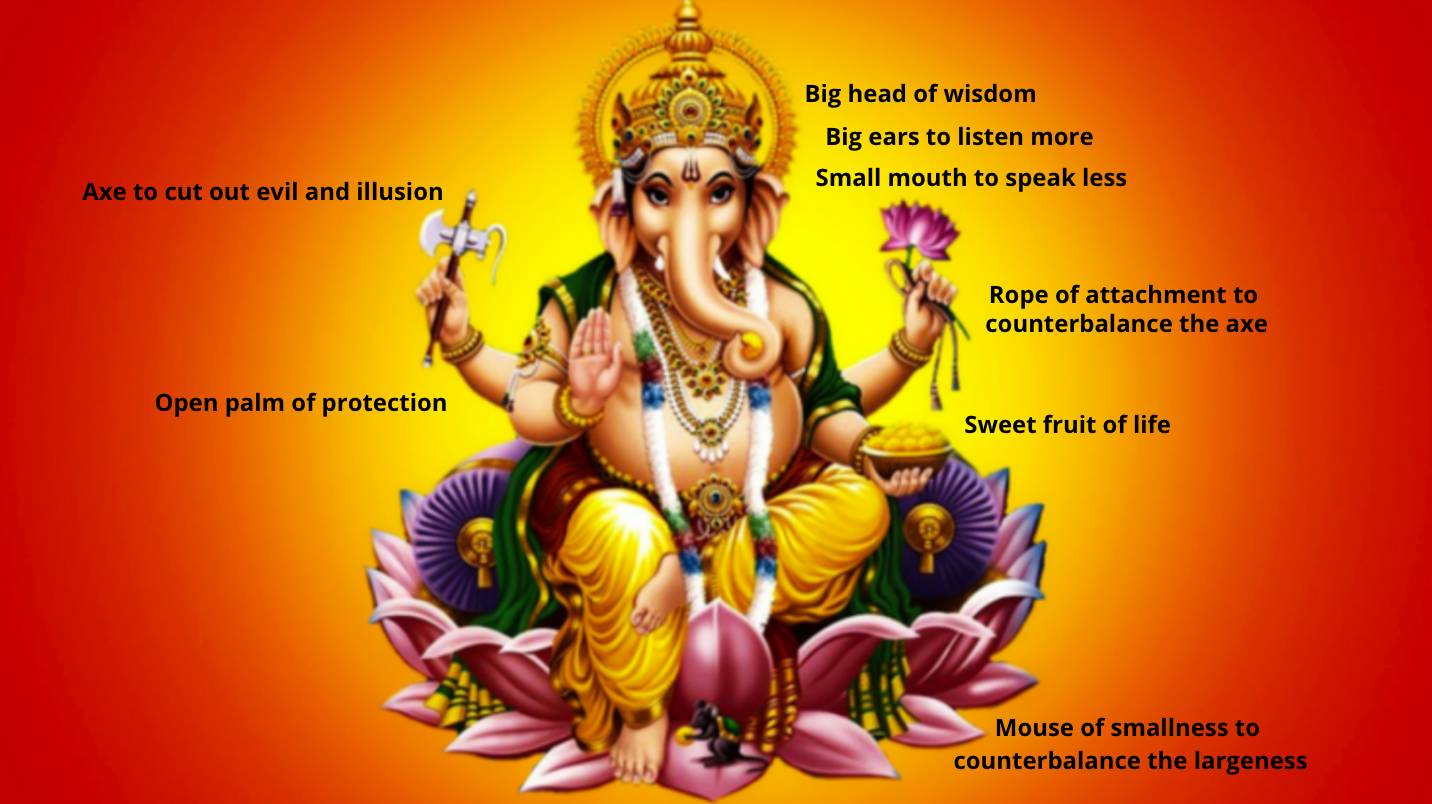

Ganesha stands out unmistakably among any pantheon of gods, with his prepossessing elephant head. Here is an animal widely associated with long life, strength and wisdom, not to mention a perspicacious memory. The symbolism is fairly explicit, and the disproportionate size of Ganesha’s head suggests wisdom in every way.

But a further look at the elephant noggin reveals more. His massive ears and his small, hidden mouth. Indeed, what could be a more universal indication of wisdom than to listen better and speak less?

Proverbs Eastern and Western all point to this noble disposition. And when the face of wisdom has a nose like a 6-foot garden hose, we are reminded that wisdom is unremarkable without the virtue of a good sense of humor.

Whatever happened to Ganesha’s head?

It’s impossible to study Ganesha without asking, “Where did the elephant head come from?” And sure enough, there’s a perfectly good explanation for that.

Ganesha was born the son of Shiva and his wife Parvati. Shiva is one of the three primary gods (Trimurti) of Hinduism. Along with Brahma the creator and Vishnu the sustainer, Shiva is the destroyer. Born of the gods, Ganesha actually had an ordinary human head as a child.

So one day, his mother Parvati goes up for a bath. She asks her strong, protective son to watch the door because she does not wish to be disturbed. But when Shiva comes home, the two do not recognize each other. According to one version, that’s because Parvati only just created Ganesh from a lump of turmeric, and so the two had never met.

In any case, Shiva insists on coming in to see his wife. But Ganesh refuses and says absolutely no visitors allowed. A great struggle ensues, and Shiva cuts off the boy’s head. But when Parvati finishes her bath and comes out to see what has happened, she is naturally distraught over the condition of her headless son. And she proceeds to give her husband a severe talking to.

Shocked and ashamed, Shiva rushes out of the house and into the forest. Coming across a noble-looking elephant, he cuts off its head and brings it back to his wife and her son. Then, bringing all his divine powers to bear upon the situation, Shiva carefully replaces Ganesha’s head with the elephant’s.

And then they all live happily ever after.

Grinning Ganesha: Why the big smile?

Something about the face of an elephant, it never looks angry, never overly worried. And what good is wisdom, worldly or spiritual, without the ability to relax and laugh at your own shortcomings? Ganesha’s healthy, round belly reiterates this air of joviality. He is one who laughs often and enjoys life, not overly concerned with asceticism and self-abnegation, unlike many other religious teachers.

A show of hands: What is Ganesha holding?

Now, for some deeper layers of meaning, let’s have a look at Ganesha’s busy hands. The Indian deities are notorious for their many arms and hands, and hands are such an essential and defining characteristic of man as a species. (Consider the linguistic root of words like manual, from the Latin manu, for hand.) This many-handedness, for me, signifies the super-human status of the gods. Not non-human, as Western theology often suggests, dividing us from them (or from Him), but more than human, possessing our vital characteristics, only more so.

Representations of Ganesha typically show him with four or six hands, and although depictions can vary quite widely (with up to 20 or more hands), there are a number of standard accouterments that the deity generally carries. Let’s take a closer look at each of those hands.

- One hand always holds something sweet and delicious, and it’s often difficult to see what it is exactly—maybe a mango—but it tends to be in one of the lower hands, held near the belly and the end of the trunk. Materially, this signifies, like his jolly belly, Ganesha’s ability to enjoy some of life’s sweet pleasures. But spiritually, and more significantly, it suggests the sweet rewards of mental discipline, the kinds achieved through meditation and devotional practice. This divine delicacy, something reminiscent of the Manna from Heaven, is frequently held just below the trunk, where Ganesh seems to savor its aroma.

- In the upper right hand, which we might reasonably consider to be the most important position, Ganesh is almost always wielding an axe. As with most images of destruction found in Indian mythology, this weapon is intended for chopping down evil and cutting it out of our lives. By evil, Ganesh really means to obliterate ignorance and illusion, the kinds of misunderstanding that lure us into cycles of suffering. Only by freeing ourselves from these fallacious paradigms, and misconceptions about ourselves and the world around us, can we come close to finding enlightenment. The axe of Ganesh also serves to sever the bonds of attachment, the grasping and clinging. This attachment, to both objects and ideas, constrains us like chains, confining us to a narrow worldview and preventing us from experiencing the world through clear, unfiltered eyes.

- Across from the axe, in his upper left hand, Ganesh usually holds a rope. An implement of attachment, the rope would appear to act as a kind of counterpoint to the axe, suggesting the need to strike a balance between opposites. The rope is commonly identified as a yoke for leading an animal, which offers some interesting interpretations. Some say that Ganesh has harnessed an animal that leads him to his destination, underscoring the need to follow our passions in pursuit of our goals, again counterbalancing the axe which severs our desires and attachments. But I also see the rope as a tool for taming the inner beast, channeling the restless, primal energy and putting it to constructive use, the way our ancestors did when they domesticated the ox.

- One more hand position worth mentioning, seen in the lower left hand of the Ganesh pictured above, is the open palm of protection. This virtually universal gesture of peace and providence can be found throughout the Buddhist and Hindu pantheon, as well as in the icons and images of western saints, including the Messiah himself. The protective hand reminds us of forces beyond our ken that guard our well-being.

Less than perfect: A god with a flawAnother intriguing feature characteristic of many Ganesh masks and sculptures is the broken tusk, which can mean a few different things. One interpretation has to do with accepting the good with the bad, and not demanding perfection. The single broken tusk can also be thought of as the one flaw of an otherwise perfect figure. Consider Marilyn Monroe’s dainty mole, or more significantly, the limp or scar that often afflicts a mythic hero. There are also a couple of anecdotal explanations. One reports that Ganesh lost a tusk in combat with his father Shiva. Another explains that Ganesh broke the tusk off himself to use as a writing tool in transcribing the epic Mahabharata as it was dictated to him by the sage Vyasa.

Ganesha’s Vehicle: Here comes the mouse

Various depictions of Ganesha include countless qualities and signifiers, but I’d like to finish by looking at one last element, his vehicle, the little mouse (or rat) typically seen scurrying around the god’s feet. The idea that the elephant uses a rodent as his vehicle strikes me as something like a zen koan, an irreconcilable riddle to be contemplated rather than solved. Like the Yin Yang, and numerous other symbols and stories, this partnership leads us to consider the relationship between opposites, as we must learn to embrace light and dark, good and evil, great and small, together as one.

Furthermore, the mouse of legends and lore often acts a symbol for our thoughts. Here comes the squeaky, incessant sound from inside, that inner dialog that races back and forth across the floorboards of our mind. Try as we might, this inner soundtrack cannot be silenced. Likewise, the elephant may try and stomp out the pesky mouse. But his clumsy stumps are no match for a darting rodent.

Yet, Lord Ganesha, with his superhuman cranium, has somehow managed to tame his thoughts, to quiet his mind, to control the seemingly uncontrollable. And that is the most divine feat of all. For thoughts are the forerunner of all things. Our thoughts become our reality, so when we control our thoughts we control our world.

Rodent reminders: Ganesha’s great memory

For an even more sophisticated interpretation, consider the rat. The rat is a pest, and we are pestered by our conscience. Our conscience speaks to us from the other side, reminding us of our transgressions and helping us distinguish between right and wrong. A healthy, well-developed conscience can guide us in our actions and our choices, and this guidance is the vehicle on which an enlightened creature moves forward.

Take a good look at the elephant god. Smile at his flappy ears and laugh at his dangling trunk. But also meditate on his wisdom and his mental prowess. Invoke him for strength and courage. Follow his example, learn to overcome the illusions and accept the contradictions, and soon you will be removing obstacles on your own.

Shopping for Ganesha statues and artwork

Hinduism accepts thousands of different deities and countless variations of each god. So they have no orthodox or correct version of Ganesh. And unlike Islam, for example, they obviously have no strict qualms against depicting their gods in artwork and imagery.

So if you’re looking to decorate your home, altar or yoga studio with an uplifting likeness of the great elephant god, don’t concern yourself with rules and regulations. Just find a Ganesh that resonates with your soul, one who emanates the right sort of energy that you’re aiming to propagate.

Whether he’s joyful and resplendent or peaceful and meditative, it’s all good. Sometimes Ganesh is dancing, sometimes he’s lying in repose, sometimes he’s reading a book. If you don’t have a metaphysical shop in your neighborhood, you can find a huge selection at Amazon.

Besides his attitude and position, you’ll also want to think about the materials. Personally, I prefer the bronze statuary, hefty and regal, but generally more expensive. Wooden Ganeshes also have a nice look and feel. And for the most affordable statuary, the resin Ganeshes come in a great variety of styles and colors.

We’d love to hear about your special connections with the glorious Ganesha. Let us know in the comments section below.

Further Reading

If you enjoy Eastern philosophy and symbolism, you’ll also want to check out the following articles.

- Om is where the Heart is: Meditations on the One

- Meanings in the Mandala: Roadmap of the Mind

- Buddhist Thangka Paintings: Meaningful and Sublime

- Archetypal Dimensions of Kermit the Frog

- Bamboo Symbolism and Mythology

Ganesh’s big belly is an attribute he shares with Hapi, the Egyptian God of the Nile, Hapi has one female breast and a big tummy which is suggestive of his copious shitting – this symbolises the sediment that washes down the Nile, making the fields so fertile (something the Aswan dam has seriously interfered with). So I wonder whether Ganesh, with his meandering trunk, was originally a god of rivers. After all, elephants love rivers, as they have no sweat glands, so it is one way of cooling off. I have a post about Hapi on my journal – anthonyhowelljournal.com – and a post about Ganesh.