To encourage the reduction of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the carbon credit trading system incentivizes farmers and industrialists to initiate and operate carbon-negative projects, rewarding them with monetarily valuable credits. At the same time, polluting enterprises pay a kind of penalty by purchasing these credits to offset their own greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Bamboo cultivation has earned great attention for its ability to capture and sequester atmospheric carbon, and many now look to it as a way to earn money in the form of carbon credits. But capturing carbon and earning validated carbon credits in accordance with strict international standards are two very different things.

To earn carbon credits by growing bamboo, the farm or forest project must undergo a costly and strenuous process of scrutinization and validation in compliance with strict regulations defined by organizations like Verra or Gold Standard. For every ton of carbon sequestered, the project developer can earn one carbon credit, which they can sell through various channels for approximately $10 to $50 each. Estimates on the number of credits one can earn per acre per year vary widely, but experts agree that the project probably needs to be thousands of acres in size to justify the expensive verification process. Other strategies have proven more effective and attainable, including turning bamboo into biochar to generate high-value Carbon Removal Credits.

NOTE: This article first appeared in March 2022, most recently updated in March 2024.

The carbon credit system

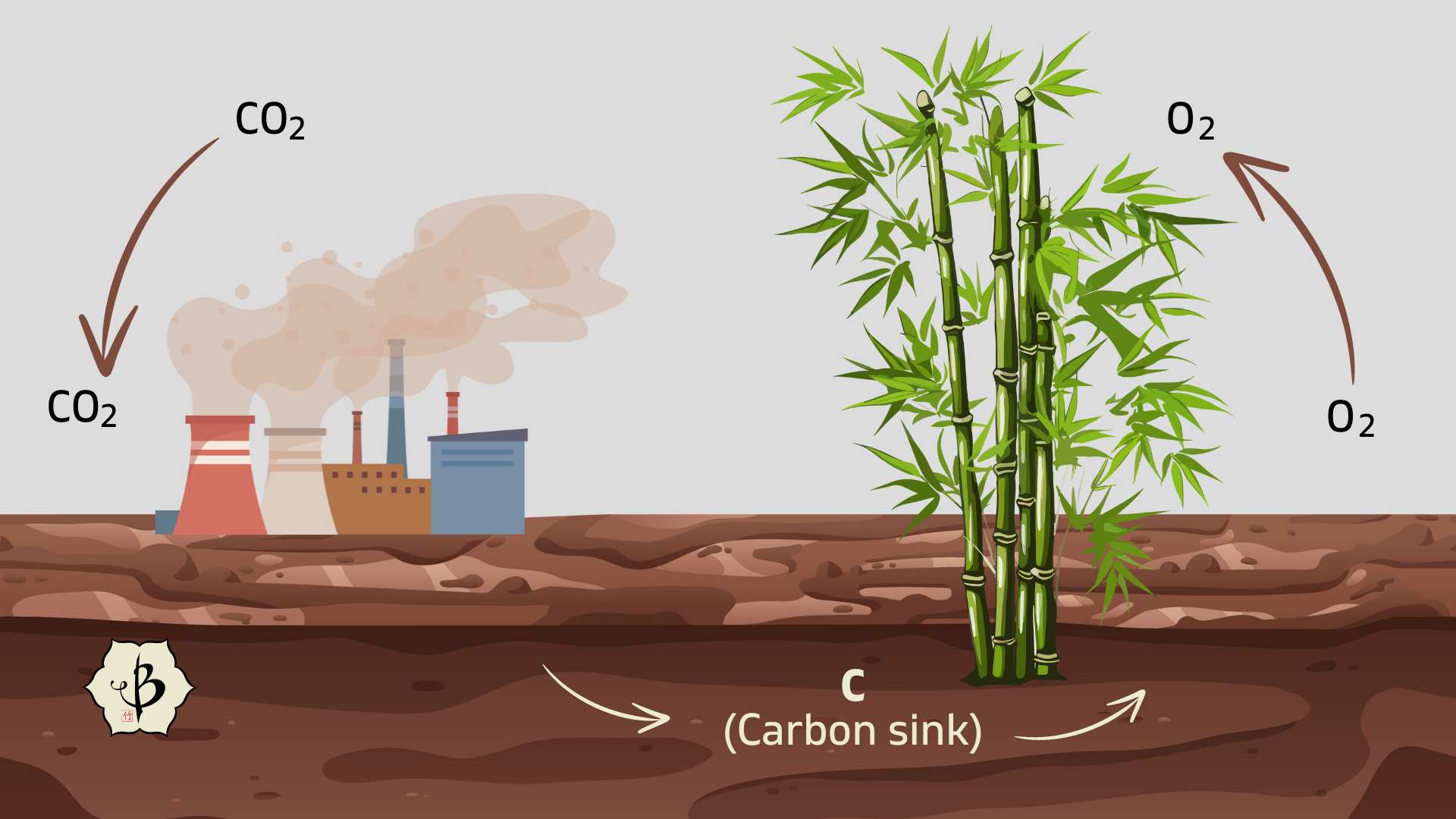

The simple principle behind carbon credits is that companies and operations that emit excessive quantities of CO2, exceeding certain levels based on international treaties and local regulations, can purchase credits to offset their emissions. These credits are generated by projects that are carbon negative, in other words, they are removing carbon rather than adding it to the atmosphere.

A single carbon credit represents one metric ton of carbon that is being retained in biomass, lumber substitutes, or alternative fuel sources, and therefore not getting released into the atmosphere and contributing to climate change and global warming.

The Kyoto Protocol introduced the concept of carbon credits in 1992 as a tool to help promote the removal of CO2 from the atmosphere. But the carbon trading market really came to life after 2005, when a Voluntary Carbon Standard (VCS) was established, creating “non-Kyoto” credits, which are still third-party verified but do not satisfy the standards of the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism. After 2020, the Paris Agreement superseded the Kyoto Protocol, essentially maintaining the same carbon offset system.

Carbon credits effectively give an entity permission to emit a certain amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) or the equivalent amount of other greenhouse gasses (CO2e). Because some companies are compelled to acquire these credits in order to comply with emissions standards, their purchase can be interpreted as a kind of fine or a carbon tax, while carbon-negative projects receive a monetary reward. In this case, companies that fail to meet emission mandates, either by purchasing credits or reducing emissions, or both, are subject to fines and legal penalties. As of 2024, the preponderance of Carbon Credits are traded on the voluntary market, but a compliance market will emerge in the next few years, as stricter regulations come into effect.

Carbon credit classification: Avoidance, removal, and additionality

It’s important to understand that carbon credits, or carbon offsets, can be sorted into two distinctive categories. First, there is carbon avoidance, which is where a project avoids the creation of additional CO2. Examples of this classification include a solar energy plant or a REDD+ forestry protection project. Solar power effectively produces electricity without the GHGs that would have been emitted by a comparable power plant running on fossil fuels. That’s avoidance, and we need more of it to mitigate Climate Change.

More important, however, is carbon removal, which actually pulls CO2 out of the sky, either through some high-tech innovation or by way of good old-fashioned photosynthesis. Planting new forests, and bamboo in particular, is one of the best examples of this. These are classified as ARR projects (Afforestation, Reforestation and Revegetation). Few things are more efficient at collecting CO2 and generating oxygen than a healthy forest. And because grows faster than any woody plant in the forest, it’s also capable of removing carbon more quickly than any other plant or tree.

Where it gets especially complicated is when you’re dealing with a project that involves protecting an existing forest. In this case, you have to make an educated guess as to what would happen to the forest if it were not being protected. Would it get cut down? If so, how much and how quickly, and what would replace it? And what would the new carbon footprint of that piece of land look like?

To avoid this dangerous guess, carbon credit certification requires an element of additionally. This means you can’t earn credits on forestry and other activities that are already there. You have to show that you are making a positive contribution. And then you earn credits on the difference between what carbon removal or avoidance was already happening, and what your project is able to add.

Certification of carbon credits from bamboo

When managed properly, a forest or plantation of bamboo can absorb large amounts of CO2 and trap it in its underground roots and aboveground biomass. This fact is fairly well recognized and understood. But measuring that quantity of CO2 and verifying it through an accredited, third-party agency can be enormously complicated.

In order to be certified, a bamboo grower must prepare a detailed Project Design Document (PDD), which must clearly outline, among other things, the intention to generate carbon credits. As the project moves forward, meticulous records must be kept regarding every aspect of the land management, planting, and harvesting processes.

After two years or more, the verifying team will typically come and examine the land, plants and soil. Auditors will scrutinize the records to see that everything is being done according to the best practices. In addition to the extra record-keeping on the part of the landowner, the verification process can cost around $25,000 per project.

The rule of thumb suggests that the carbon credit earnings do not justify the cost of verification unless you are producing at least 20,000 credits (or capturing 20,000 tons of carbon) per year. For a bamboo grower, this would usually require a minimum of a few thousand well-managed acres.

One of the key criteria in the accreditation process is the notion of additionality. Part of this includes proving that the carbon credit scheme is integral to the project, and that the project would not have occurred without it.

In other words, you can’t launch a bamboo plantation for the sole purpose of producing lumber products, for example, and then apply for carbon credits several years down the line, as something of an afterthought. Likewise, someone who has a piece of land with vast acreage of bamboo, which has been there for 10 or 20 years, can’t simply go and claim carbon credits on this already existing carbon sink. One must be conducting additional carbon removal that would not have occurred otherwise.

It’s also important to know that carbon projects can be grouped. That is to say, you can have multiple sites and bundle them as one project, so long as they are conducting the same kinds of carbon removal activities. Grouping has the advantage of making carbon credits available to smaller farmers who would otherwise be put off by the high cost of assessment and the cumbersome preparation of a PDD.

Counting bamboo carbon credits: How many tons per acre?

With the enticement of earning valuable credits for every ton of carbon sequestered, prospective farmers are all asking: How many tons of CO2 per acre of bamboo?

Answers to this question can vary wildly depending on whom you ask. Bamboo Logic, based in the Netherlands and farming bamboo in Portugal, puts the number at 48 tons per acre.

One company in Florida states on its website that its bamboo farms collect 400 tons of carbon per acre per year. If you do the math, that could bring in as much as $20,000 per acre (based on carbon credits selling for $50 each). Numbers like this could convince farmers across the south to ditch their corn, cotton, citrus, and tobacco, and start planting bamboo instead.

Not so fast though. According to a range of projects described by INBAR, including those that have been measured in China, verified carbon sequestration through bamboo forestry looks more like 20-40 tons per acre per year. Earnings of this level make the idea of farming bamboo for carbon credits somewhat less appealing.

In any case, farmers should look at the potential earnings from carbon credits as secondary or supplemental to whatever their primary business strategy is, whether they’re conducting reforestation, manufacturing bamboo floors, or milling bamboo into paper.

Verified bamboo projects

Given the relatively recent interest in bamboo cultivation and the great complexity involved in validating a project for carbon credits, the number of bamboo projects being certified for carbon credits remains very small. As of 2022, EcoPlanet Bamboo‘s reforestation project in Nicaragua was the only bamboo farming or forestry project to be fully certified for carbon credits. In 2021, EcoPlanet received certification for 250,000 tons of CO2e. But many more bamboo projects in Ghana, Rwanda, South Africa and the Philippines are now in the application process with Verra and Gold Standard.

Check out our deep dive into Bamboo Carbon Farming Projects on YouTube, for more details.

According to EcoPlanet COO Camille Rebelo, the company currently has 4 other projects in 3 different countries in the validation pipeline. With these projects, they will continue to remove significant quantities of carbon over the next decades. But she warns individual farmers that in most cases the onerous verification process makes the likelihood of commercializing bamboo with carbon credits quite low.

A few projects in China claim to be certified, but unlike the methodology approved by Kyoto’s Clean Development Mechanism, China’s domestic certification process is not nearly as rigorous, nor is it internationally recognized. Other bamboo companies in Europe and South America have also expressed an interest in carbon certification, but again, the validation process has thus far proven prohibitive.

In the past year, the interest in generating carbon credits with bamboo has exploded, and I speak to people every week who are planning bamboo agroforestry projects in the tens of thousands of hectares. These projects are incentivized almost entirely by carbon financing, and that’s great. But in many cases, I’m not sure if those behind the projects have a complete understanding of what it takes to farm bamboo at that scale. And so far, the majority of these projects are still very much in the theoretical or aspirational stage. They have yet to produce any carbon credits.

Besides EcoPlanet Bamboo, the only organization I know of that has successfully created carbon credits from bamboo is a Swedish-based company called Planboo. Full disclosure: I was so excited to learn of Planboo’s success in this area, that I started working with them in the middle of last least, and I’m currently on their payroll. See the “Bamboo biochar” section below for more details.

Mandatory (CER) vs voluntary (VER) carbon markets

In addition to fully accredited carbon credits, such as those issued by nonprofit entities like Verra, there are also voluntary carbon offsets that do not satisfy the rigid standards of the Kyoto Protocol. Platforms like PuroEarth and Patch.io offer these offsets to companies who voluntarily elect to offset their carbon emissions. VERs (Voluntary Emission Rights) look great in a company’s portfolio, but only CERs (Compliance Emission Rights) enable a company to meet strict, international emission requirements.

The mandatory or compliance market is regulated through international and regional carbon reduction schemes, such as the Clean Development Mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol, the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS) and the California Carbon Market. Meanwhile, programs like Puro Standard, the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), the Gold Standard, and the Climate Action Reserve help to facilitate a reliable market for voluntary offsets.

Voluntary and unofficial carbon offset certificates come in many forms. Non-profit organizations like PuroEarth offer a marketplace for CO2 Removal Certificates (CORCs), verified and issued by third-party entities. In Colombia, Guadua Bamboo rewards those who want to Adopt-a-Bamboo with an estimated carbon offset certificate based on the company’s own calculations.

Companies that voluntarily buy these types of offsets do so for the sake of corporate social responsibility, i.e. to show their support for environmental causes or to meet their own carbon neutrality goals. But VERs and CORCs do not bring businesses into compliance with official mandates set by local governments and international treaties.

In the voluntary market, carbon-capturing projects are free to set their prices as they please, and companies can shop for offsets based on the nature of the project. For example, a tech company in California may wish to diversify its portfolio by supporting wind energy in Iceland, biochar from Planboo in Thailand, and PEFC-certified timber from Finland. CORCs from a bamboo project in Florida could be more or less appealing than equivalent certificates from another bamboo project in Ethiopia, for any number of reasons.

Bamboo biochar and carbon credits from Planboo

Bamboo biochar is a prime example of a product that takes atmospheric carbon and fixes it in a stable substance, where the carbon will remain for a thousand years or more. When bamboo undergoes pyrolysis, it is transformed into a charcoal-like product made up of around 80% carbon. That substance gets planted in the ground as a soil additive, or a fertilizer substitute, and offers a host of nutritional benefits for farmers, enhancing soil health and boosting crop yields, while reducing the need for chemical fertilizers.

Biochar also sequesters a significant quantity of carbon, and because that carbon can be measured and verified in a relatively straightforward fashion, Planboo has been able to generate genuine Carbon Dioxide Removal Credits (CDRCs) for bamboo projects in Africa and Thailand, as well as other types of farms in Sri Lanka. Because carbon removal with biochar is more measurable and certifiable, and more permanent in the soil, these CDRCs fetch a higher price, up to $200 each.

Carbon displacement in hard goods

The manufacture of engineered lumber from bamboo is another way to keep CO2 out of the atmosphere. Approximately half the weight of a durable bamboo lumber product is stored carbon, such that 1 cubic meter stores about 1.6 tons of carbon over its 30-year lifetime.

Companies engaged in these kinds of activities can issue unofficial certificates as well. But at this time, no official methodologies exist to measure and verify these carbon offsets.

Fuel for thought

To learn more about the ins and outs of bamboo cultivation and the fast-growing international bamboo industry, take a look around our website. You might find some of the following articles especially interesting.

We have a database of Bamboo – 5500Hectare – in India – & – want to get the CCPs certified – to be linked to our Carbon Credits Exchange – Please suggest some verification agency

P D Sharma

+919817579591

Dexa-Exchange

India & UAE

Verra and Gold Standard are the verification agencies that most projects rely on.

Have you looked into the Nature Conservancy pilot projects to allow small land owners to “coop”their carbon credits for sale? Pennsylvania and soon Tennessee will have it avaiable.

Sounds interesting. Be sure to do your homework before delving into any of these carbon credit schemes. A lot of programs are unable to deliver on what they promise.

Dear Sir/Ma’am,

Wonderful day and Happy Holidays!

I was wondering whether Bamboo Batu would be interested in investing/funding in 1,000 hectares of Indigenous People (IP) property in Marilog District, Davao City, Philippines, appropriate for bamboo plantation carbon credits.

I am originally from the Philippines and currently work as a freelancer in the United States.

Please let me know if Bamboo Batu has interested investors.

Thank you very much!

Best,

Bert R. Ginampos

M: +1 813-500-1310

Hi Bert, We cannot fund your project, but we can advise you on how to get your bamboo farm grouped into another carbon project to earn revenue from the credits. Let’s chat.

Very interesting topic, I have learned a lot bamboo and carbon credit. I would like to play a role by going into bamboo plantation in Africa. Thanks

Good luck and godspeed, my friend! The best time to plant bamboo is about 4 years ago. The second best time is now!

Hello Fred. It is indeed a great post on understanding bamboo cultivation and carbon credit. I am from India and am keen on exploring the possibility of developing Banboo cultivation projects with a socio-economic objective where apart from our business interest, we help farmers to empower their lives. Please let me have your contact details to discuss the subject further. We are also interested to know more about producing value-added products from Bamboo i.e Biochar/Beer/Wine/Paper/Fabric/Cosmetics/ Biofuel etc. ,

Thank you, Sunil. I’d be happy to set up a consultation.

I have 15 acres and I have a lot of bamboo growing wild and I would be interested in talking to you or finding out what I need to do about the carbon credit or what would be best for me to do thank you

Hello Fred. Thank you for the post on understanding bamboo cultivation and carbon credit. I am from India and exploring the possibility of developing Bamboo cultivation projects with a socio-economic objective where apart from business interest, the farmers are able to benefit from carbon credits.