The realm of bamboo is vast and varied. With more than 1,400 species to keep track of, it can take some serious time and energy to wrap your head around it. You don’t need to become an expert before your plant your first bamboo in the ground, but there are some basic parameters you should be aware of. One of the most important things to understand is the difference between running bamboo and clumping bamboo.

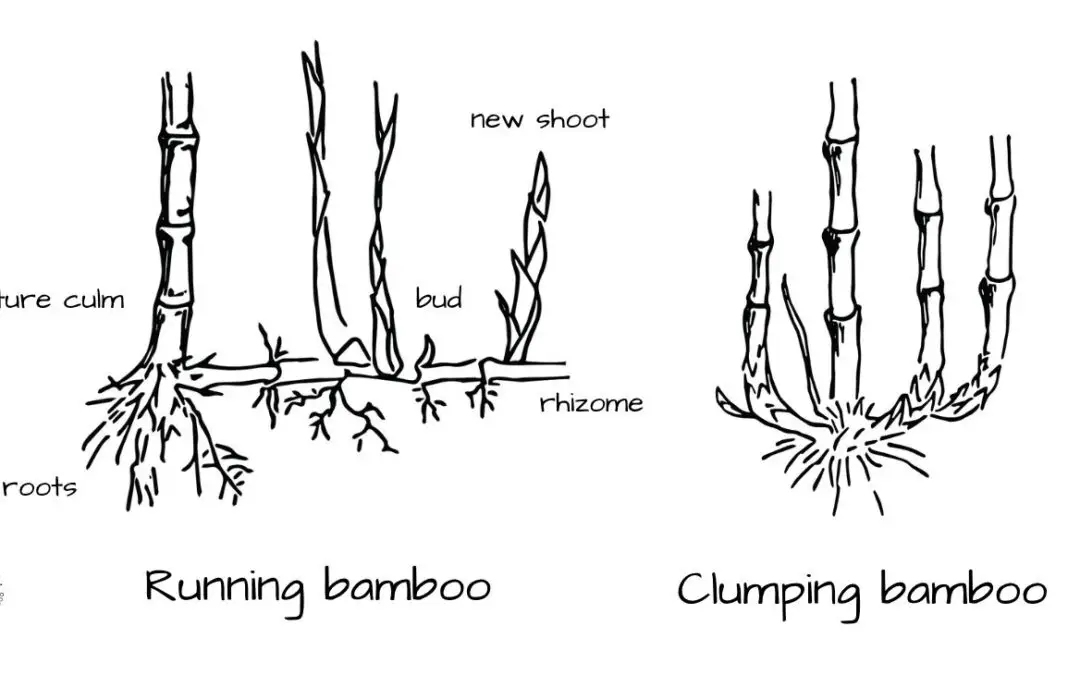

While there are close to 2,000 species and subspecies of bamboo, it’s easiest to start by dividing them into two groups: runners and clumpers. Running bamboo has an expansive rhizome root system that tends to spread out. These rhizomes sprawl ever outward, and if left unchecked, can take over a large area becoming something of a nuisance. Clumping bamboo, as the name implies, is generally far more manageable and compact. The rhizomes of these varieties cling closely together, posing little threat to the rest of the garden. For these reasons, many gardeners prefer clumping, or non-invasive bamboo. But the dangers associated with running bamboo are often overstated.

NOTE: This article first appeared in July 2021, most recently updated in May 2024.

Bamboo types and varieties

To say that there are just two different kinds of bamboo is quite an oversimplification. At the same time, it’s a pretty useful and helpful way to get a handle on this multifarious subfamily of grasses.

In truth, there are nearly 100 different genera of bamboo. Some genera only have a handful of species, while others have more than 100. The diversity of bamboo is so great that authors and experts have a hard time agreeing on exactly how many species and genera there are. And most of the time, amateur gardeners will find it very difficult to tell them apart.

Bamboo comes in all shapes and sizes. There are species that grow to the size of a chopstick, and there are those that exceed 100 feet in height. There are bamboos from the Amazon rainforest and others from the snowy Himalayas. Some bamboo is native to the southeastern United States, and some is endemic to the highlands of sub-Saharan Africa.

But for the purposes of classification, botanists organize and identify bamboo according to its physiology. That is, they look at the shape of the rhizomes, the structure of the flowers, and the configuration of the branches. So if you have a few bamboos belonging to the same genus, they will all have the same rhizome type (either running or clumping), the same kinds of flowers, and the same arrangement of branches. Although they might be considerably different in size.

Running bamboos

In botanical jargon, running bamboo belongs to the Arundinarieae tribe and has what we call leptomorph or monopodial rhizomes. Basically, this means that the rhizomes extend outward, away from the main plant, parallel to the ground. The rhizomes are shallow and you’ll often see them rising up out and of the soil. In most respects, the rhizomes are very similar to the stems (or culms) that grow upward. They have the same kind of segmentation, with nodal joints, and are generally hollow on the inside.

The old adage says that in the first year bamboo sleeps, in the second year it creeps, and in the third year it leaps. That’s because the plant initially concentrates its energy on establishing a robust network of rhizomes. So if you’re not paying careful attention, you might think it’s a clumper.

But if you look closely, you’ll discover leggy rhizomes stretching all around the plant. And after a year or two, the rhizomes will start producing fresh shoots, sending them straight upwards. At this point, you’ll begin to see the extent of the rhizomes that had been spreading silently underground.

This aggressive growth habit has earned running bamboo a rather nasty reputation. But the dangers of planting running bamboo are somewhat exaggerated. See the section on how to bamboo, below.

Temperate bamboo

The phrase temperate bamboo is often used synonymously with running bamboo. Unlike the vast majority of clumping bamboos, running bamboo tends to come from cooler climates. Therefore, most running bamboos are very cold-hardy and can survive snowy winters and montane climates.

This is one of the reasons why running bamboos are more popular, especially in certain parts of the world. But there are definitely some exceptions to this rule. See our in-depth article on cold-hardy clumpers.

Identifying running bamboo

The most common genus of running bamboo is Phyllostachys. This genus includes about 50 species, and countless cultivars or subspecies. Because of its aggressive growth habit, Phyllostachys has successfully established itself all across the world. In addition to spreading effectively in your garden, it’s very easy to propagate new plants from these long, circuitous rhizomes.

Consequently, you can find P. aurea (Golden Bamboo) growing in gardens and nurseries all around the world. Its easy propagation also makes this one of the least expensive bamboos. Cheap and plentiful, these are two good reasons why people end up planting this variety of bamboo, or running bamboo in general.

If you want a plant that will grow fast and quickly fill in a certain area of your garden, runners like Phyllostachys are a great choice. But if you’re afraid of having a bamboo plant that will spread too quickly, then you’ll want to avoid it.

The good news is that Phyllostachys is probably the easiest genera of bamboo to recognize. The culms and rhizomes have distinctive sulcus grooves. These are the narrow indentations that run along the internodes, between the joints, on alternating sides of the plant. If you can find these grooves on your bamboo, then you know it’s a Phyllostachys, and therefore a runner. But there are plenty of running bamboos that don’t have this groove.

Running bamboo genera

Here’s a quick list of the most common genera of running bamboos.

- Arundinaria: Includes 3 species native to the Deep South of the U.S.; relatively vigorous runners

- Chimonobambusa: Asian bamboos with unusually shaped culms, including Square Bamboo; relatively vigorous

- Indocalamus: Small to medium-sized bamboos that often look like clumpers but gradually spread out

- Phyllostachys: The most prolific genus of running bamboo, mostly from China and Japan, with an enormous variety of species; vigorous growth habit

- Pleioblastus: Mostly dwarf bamboo, small in stature but quick to spread; mostly native to China; relatively vigorous

- Pseudosasa: Medium-sized, Asian varieties, like Arrow Bamboo, that make popular ornamentals; moderate runners

- Sasa: Primarily dwarf bamboo species of Japanese origin; relatively vigorous

- Semiarundinaria: Medium-sized, Asian varieties, like Temple Bamboo, popular as ornamentals; moderate runners

Containing running bamboo

It’s true that running bamboo has a way of running amok and potentially wreaking havoc on an otherwise orderly garden. But it’s not as bad as people say. And with a little forethought, a running bamboo plant can be well-contained.

In fact, bamboo is not actually invasive in the strict sense of the word. Invasive species will arrive in a foreign habitat and cast their seeds all about. As they sprout up across this new landscape, they don’t face their ordinary population of competitors. So they are able to proliferate and choke out the native species, often throwing sensitive ecosystems out of balance.

Bamboo, by contrast, really only spreads with its roots and rhizomes, not by casting seeds. Therefore, it’s only capable of invading a very localized area. It’s not going to go wild and take over the mountainsides. If that were the case, bamboo would have overtaken the world by now.

But it can certainly send roots and shoots all over your lawn and your flower beds. It also has of way of sneaking under the fence into your neighbor’s garden, or even breaking through the sidewalk.

To stop this kind of invasion, the two best options are to plant a rhizome barrier or to dig a trench around your bamboo. Check out our in-depth article on bamboo containment.

Clumping bamboos

Instead of the long rhizomes that stretch out like tentacles, clumping bamboo typically has tightly-growing rhizomes with a U-shape. Botanists refer to these as pachymorph or sympodial rhizomes. They bend upwards right away to form shoots, rather than building underground networks. In terms of classification, clumping bamboo belongs in the Bambuseae tribe. In most cases, a clumping bamboo will reach a certain size, a maximum area, usually around 10-20 feet across, and then stop spreading.

If you see a grove of bamboo with the culms all clustered close together, it’s easy to assume that it’s a clumping variety. But don’t be too sure. You’ll need to poke around in the soil a bit and see what the roots are up to and what the base of the culms looks like. You’ll also have to confirm that there are no surreptitious rhizomes running around. Running rhizomes normally grow within a few inches of the surface, so they’re not difficult to detect, once you start looking.

Clumping bamboo genera

There is a tremendous variety of clumping bamboos out there, but many of them are less suitable as garden ornamentals. Here are some of the more common genera.

- Bambusa: One of the most widespread and diverse genera, with over 100 species distributed all over Asia as well as Australia and the Pacific Islands

- Chusquea: Native to the New World, from Southern Chile to Northern Mexico, with unusually solid culms

- Dendrocalamus: Among the most massive of all bamboos, primarily native to India and Southeast Asia

- Fargesia: Native to the Himalayas, among the most cold hardy of all bamboo varieties

- Gigantochloa: Mostly giant bamboos from Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands

- Guadua: Neotropical bamboo genera, including the most economically important bamboo of the New World

- Himalayacalamus: Includes several exotic and colorful bamboo species from the Himalayan foothills

- Otatea: Mexican Weeping Bamboo is the best-known member of this Meso-American genus

- Schizostachyum: A tropical genus of bamboo indigenous to Southeast Asia, Pacific Islands, and Madagascar

Tropical bamboo

As you can see from the list, most of these genera are native to warmer climates. In fact, clumping bamboo is sometimes called tropical bamboo, the same way we refer to runners as temperate bamboo.

Because they prefer the tropic and subtropical climates, gardeners in North America and Europe have a hard time growing many of these. The truly tropical varieties, like Dendrocalamus, Gigantochloa, Guadua, and Schizostachyum, will not survive freezing temperatures for any length of time.

But like many things from the tropics, some of these clumping bamboos can grow to enormous proportions. Species of Dendrocalamus commonly exceed 100 in height, and some have been known to reach an astonishing 150 feet. But unless you live somewhere like Southern Florida, you’ll find it challenging to keep these specimens happy.

The genus Bambusa includes tropical and subtropical species. While some varieties will incur frost damage whenever temperatures drop below 30, others will do well so long as it doesn’t get below around 20º F. Species like B. oldhamii, an impressive timber bamboo, can thrive in most parts of the West Coast and the Deep South, but not so well in Colorado or Minnesota.

Outliers

As writers and scientists, we like to impose our order on nature. But it’s not always that easy. The line between runners and clumpers can sometimes get blurry. As it happens, we have clumping bamboos, so-called tropical bamboos, native to the high Andes and the Himalayas, which can withstand temperatures as low as -20º F.

If you’re growing bamboo in Canada or at high elevations, something from the genus Fargesia will be your best bet. But if you want a clumping bamboo that can handle the heat as well as the cold, you might try some Chusquea from South America. Many of the popular species of Chusquea will survive from 0º all the way to 100º F.

You should also be aware of what we call “open clumpers”. These varieties of bamboo have the pachymorph rhizomes characteristic of clumping bamboo, yet they have a tendency to spread out into pretty wide clumps. Many species of Himalayacalamus exhibit this trait, as do some varieties of Dendrocalamus, among others. Furthermore, species from the genus Indocalamus are technically runners, in the tribe Arundinarieae, but they often behave more like clumpers.

Further reading

If you found this article on running and clumping bamboos helpful and informative, please consider sharing the link. You might also want to read up on other topics related to bamboo maintenance and cultivation.