There’s something magical and otherworldly about a thriving grove of bamboo. Surround yourself with this dazzling grass, and it has a way of transporting you to another time and place. Bamboo has an exotic feeling, and a connection with the far-flung corners of the world. But where exactly does it come from? The answer may not be quite as straightforward as you would think.

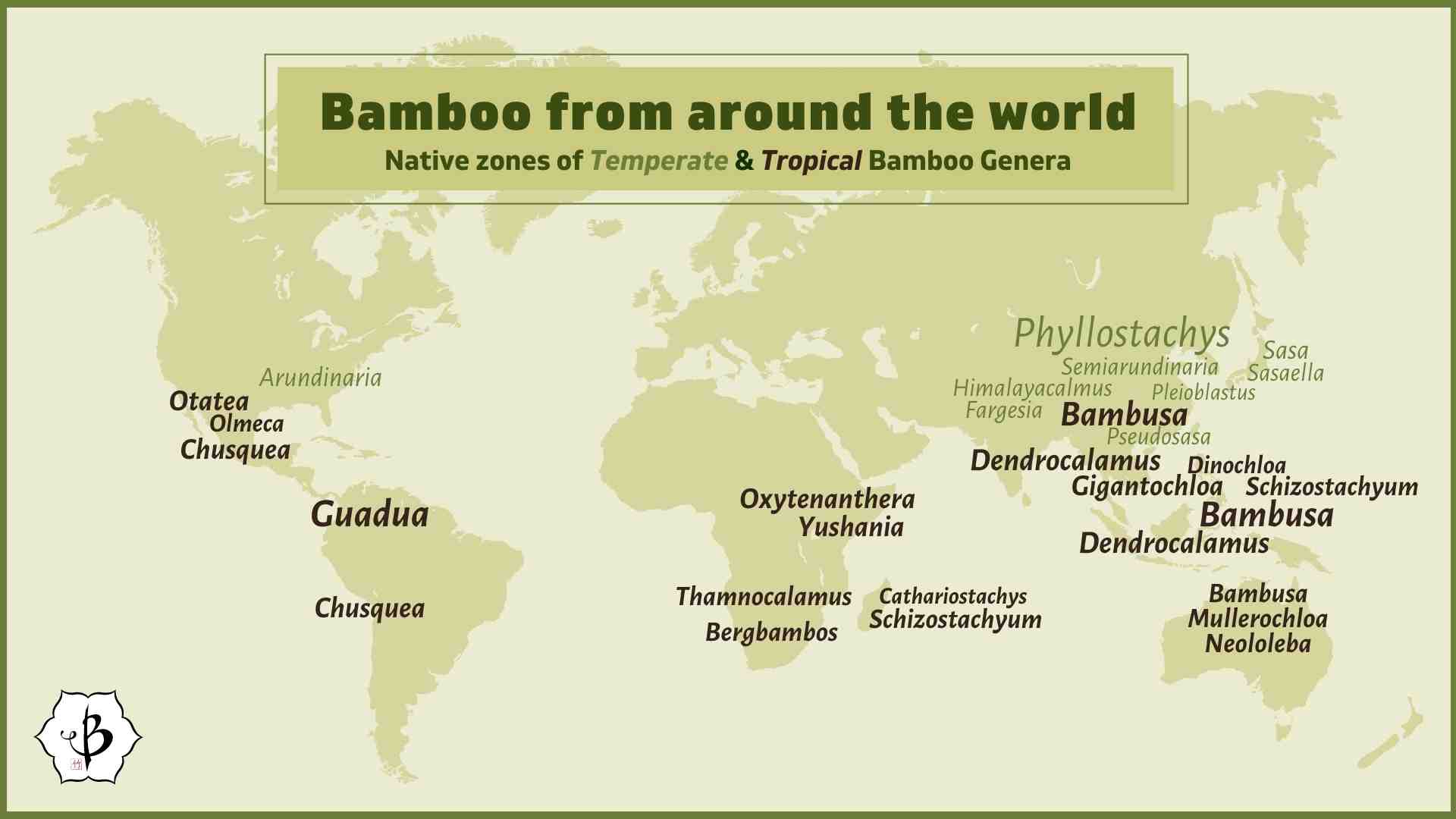

There are actually endemic populations of bamboo on every continent but Europe and Antarctica, including parts of Africa and northern Australia. We tend to think of bamboo as an Asian plant, and in fact, Asia has more native species of bamboo than any other continent. Between China, India, Japan and the Indonesian archipelago, the diversity of bamboo genera is quite vast. Certain bamboos prefer the tropics of Vietnam and Malaysia, while others are indigenous to the cool slopes of the Himalayas. We also know a handful of bamboo strains unique to such remote islands as Madagascar and New Guinea. In the Western Hemisphere, a significant number of bamboo varieties have originated in Central and South America, and even a few species have their roots in the eastern United States.

In the following article, we’ll examine the widespread domain of this pervasive subfamily of grasses. And we’ll explain which bamboos grow where. There are a few generalizations we can make about the bamboos growing in different continents and climate zones.

The astonishing diversity of bamboo

Bamboo is a perennial grass, belonging to the family Poaceae and comprising its own subfamily Bambusoideae. Botanists like to divide the subfamily into three tribes: Bambuseae (tropical woody bamboo), Arundinarieae (temperate woody bamboo), and Olyreae (tropical herbaceous bamboo). Among these three tribes, the experts recognize anywhere from 90 to 120 different genera (plural of genus) of bamboo, with about 1,400 different species.

In classifying bamboo, many different characteristics have to be considered. The origin and distribution of the genus or species is one important factor. So when we talk about where bamboo comes from, the easiest way is to study them genus by genus. From looking at the three tribes of bamboo mentioned above, we can already see that some bamboos come from the tropics and others come from more temperate climes. And as we’ll see below, certain genera also belong to different regions and continents.

Bamboo by climate: Tropical vs. temperate

If you’re growing bamboo, understanding the plant’s native climate is much more important than knowing what country it came from. In the most general division, plants from the Bambuseae tribe are tropical or subtropical, and those in the Arundinarieae tribe are temperate, and more likely to withstand sub-freezing winters. (Olyreae species are also tropical, but these herbaceous bamboos are something of a novelty. They have not been naturalized outside of their native habitat, primarily the Amazon basin.)

In addition to their cold hardiness, the distinction between tropical and temperate bamboo has a strong correlation to their growth habit. Tropical bamboos typically have clumping rhizome roots, while temperate bamboos have running rhizome roots.

An exception to this rule is the genus Fargesia, which is a temperate bamboo (of the Arundinarieae tribe). These are some of the most cold-tolerant of all bamboos. But unlike other varieties of Arundinarieae, they have clumping, non-invasive root systems. Mostly they are native to central and southern China, often in higher elevations. But you can also find them growing in tropical zones like Vietnam. The genus Himalayacalamus is another interesting exception, made up of temperate, clumping bamboos, native to the lower slopes of the Himalayas.

Clumping bamboos of the tropics

Apart from those botanical outliers, if you’re looking for a clumping bamboo, it will be helpful to live in a warmer climate. In terms of bamboo, clumping is practically synonymous with tropical. Still, this only refers to the conditions in their native habitats. Not every “tropical” bamboo requires tropical or subtropical weather to survive, but most of them are frost sensitive and will have a pretty hard time in places that get snow.

Many species of the genus Bambusa are strictly tropical or subtropical, but some are hardy down to about 20º F. Members of the genus Chusquea, clumpers from Central and South America, are also surprisingly hardy, often down to 0º F. But giant bamboos in the genus Dendrocalamus or Schizostachyum won’t really make it if temperatures regularly drop below freezing. The same goes for neotropical timber bamboo like Guadua.

Running bamboos from cooler climates

If you’re growing bamboo in colder climates, like USDA zone 7 or lower, you’re probably going to have better luck with a running bamboo. Varieties like Phyllostachys, Sasa, and Pleioblastus, predominantly native to China and Japan, are very cold-hardy and can be very fast spreading. They can even grow in Canada, one of the few places that has no native species of bamboo. But they can also be invasive, which makes many gardeners uncomfortable. In many cases, however, the freezing weather tends to slow the growth and spread of an otherwise highly aggressive bamboo specimen.

Sasa kurilensis is an exceptional species of bamboo native to the Kuril Islands of northern Japan and Russia. Small in stature but resilient against inclement weather, this specimen has the northernmost habitat of any bamboo variety.

Fun fact: The most widespread bamboo

The line between tropical and temperate bamboo, as we’ve seen, is not always perfectly sharp. Genus Chusquea, for example, grows throughout Central and South America. A New World clumper, it has the widest distribution of any bamboo genus, in terms of both latitude and altitude. You can find members of this genus from 47°S in southern Chile to 24°N in Sonora, Mexico, and from sea level up to 4,000+ meters.

Bamboo by continent and country

It’s important to be familiar with a bamboo’s native climate, for cultivation purposes. But it’s also interesting to recognize bamboo’s great range of distribution across the globe. The following list, by no means exhaustive, provides a good overview of the most widespread genera of bamboo, stretching all across the planet.

| Continent | Countries and regions | Bamboo genera (tropic or temperate) |

| Asia | China, Southeast Asia, Himalayas, Northern Australia, New Guinea | Bambusa (tropical) |

| Asia | China, Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam | Chimonobambusa, Indocalamus, Fargesia, Phyllostachys, Pleioblastus, Pseudosasa, Shibataea (temperate) |

| Asia | Japan, Russia | Sasa, Sasaella (temperate) |

| Asia | India, Southeast Asia, Indonesia | Dendrocalamus, Gigantochloa, Thyrsostachys (tropical) |

| Asia | Bhutan, Nepal, Tibet, India | Himalayacalamus, Borinda, Yushania (temperate, clumping) |

| Asia | Philippines | Cyrtochloa, Dinochloa (tropical, climbing) |

| Africa | Sub-Saharan savannas | Oxytenanthera (tropical) |

| Africa | Sub-Saharan | Bergbambos, Oldeania, Thamnocalamus, Yushania (temperate, clumping) |

| Africa | Madagascar | Cathariostachys, Schizostachyum (tropical) |

| Australia | Northern Australia | Bambusa, Mullerochloa, Neololeba (tropical) |

| Central & South America | Mexico to Argentina | Guadua, Chusquea (tropical) |

| Central & South America | Mexico to Colombia | Otatea (tropical) |

| North America | United States | Arundinaria (temperate) |

| North America | Mexico | Olmeca (tropical) |

As we can see from the chart above, you can find native bamboos in virtually every corner of the earth, including five of the seven continents. Canada and Europe are really the biggest exceptions, having no native bamboo populations. Still, bamboo has managed to reach these places, by way of nurseries and botanical gardens. Fargesia and Phyllostachys are the most popular genera in those cooler regions, but certainly not the only ones.

Bamboo in Africa

Africa isn’t the first place we think of when we talk about bamboo. But there are a few varieties native to the great continent, and to the island of Madagascar. The genera Bergbambos, Oldeania, and Oxytenanthera are all clumping bamboos unique to sub-Saharan Africa.

One species of Yushania (Y. alpina) is also native to eastern Africa, although most members of that genus grow around the Himalayas. Cathariostachys is unique to Madagascar, while Madagascar and New Guinea both have species of Schizostachyum.

Bamboo in the Americas

The New World is also home to a surprising number of tropical bamboos, chiefly found in South and Central America. Mexico also have a few native genera, like Olmeca and Otatea. Even the eastern United States is home to a few native species, all runners in the genus Arundinaria.

Bamboo for your part of the world

It’s also clear that Asia is home to the greatest variety of bamboo, including the two most diverse genera, Bambusa and Phyllostachys. These are basically household names among bamboo enthusiasts throughout North America. And in most parts of the US and Canada, bamboo gardeners may be familiar with several other temperate, Asian varieties.

However, if you live somewhere like San Diego or southern Florida, zone 9 or above, then you’re open to a far wider variety of tropical and subtropical bamboos. There you can branch out into the more exotic cultivars of Dendrocalamus, Schizostachyum, and Thyrsostachys.

Exotic bamboo around the world

Searching the planet to see more unusual bamboo varieties that won’t survive in your backyard? Check out our fabulous list of the world’s most beautiful bamboo gardens. From Thailand to Hawaii to the south of France, it’s easy to plan a vacation that revolves around bamboo tourism.

Speaking of Hawaii, you may have noticed that we haven’t listed any bamboo genera as being native to the Aloha State. Although the island of Maui has some of the most amazing bamboo forests in the world, the plant isn’t exactly native. Because the islands rose out of the sea as volcanoes, all the plants on the islands actually came from elsewhere, drifting over from Japan, the Philippines and Southeast Asia. (See our in-depth article on Bamboo in Hawaii.)

Further reading

If you’d like to learn more about growing and using bamboo, why not take a look at some of our most popular articles.