In the world of ornamental horticulture, you can find some spectacular bamboo varieties that will make a great addition to your garden. But if you plant the wrong kind of bamboo, it can turn into an awful beast. And then you’ll never want to see another bamboo plant again. With around 1,500 types of bamboo to choose from, it’s helpful to know which are the most invasive varieties, so you can avoid them, and maintain a happy, healthy relationship with this noble family of grasses. Not to mention a friendly relationship with your next-door neighbors.

Not all varieties of bamboo spread so vigorously, but some species can certainly be invasive. The most invasive varieties belong to the genus Phyllostachys. These temperate bamboos, native to East Asia, have running rhizomes that can spread indefinitely. Other aggressive, running bamboo genera include Sasa and Pleioblastus, but they tend to grow much smaller. Most tropical bamboos, like genus Bambusa and Dendrocalamus, have clumping rhizomes, meaning that their roots and shoots cling closer together, usually spreading to a limited size.

This is such a concern that some states and cities have gone so far as to pass laws that regulate or prohibit certain kinds of bamboo. Although in reality, the invasive nature of bamboo has been greatly exaggerated in popular culture.

NOTE: This article first published in July 2020, most recently updated in March 2024.

Invasive species

To begin with, here’s a quick chart that identifies some of the most invasive types of running bamboo.

| Botanical name | Common name | Description |

| Phyllostachys aurea | Golden bamboo | Medium (30′) and slender (approx. 1″) culms with dense foliage |

| Phyllostachys aureosulcata | Yellow groove bamboo | Tall timber bamboo (50′ tall, 2-3″ thick) with yellow stripe |

| Phyllostachys bissetii | Bissetii | Very cold hardy, 10-30′ tall, with thick foliage |

| Phyllostachys rubromarginata | Red margin bamboo | Ideal for privacy screens, up to 40′ tall and 3″ in diameter |

Runners and clumpers

How they grow

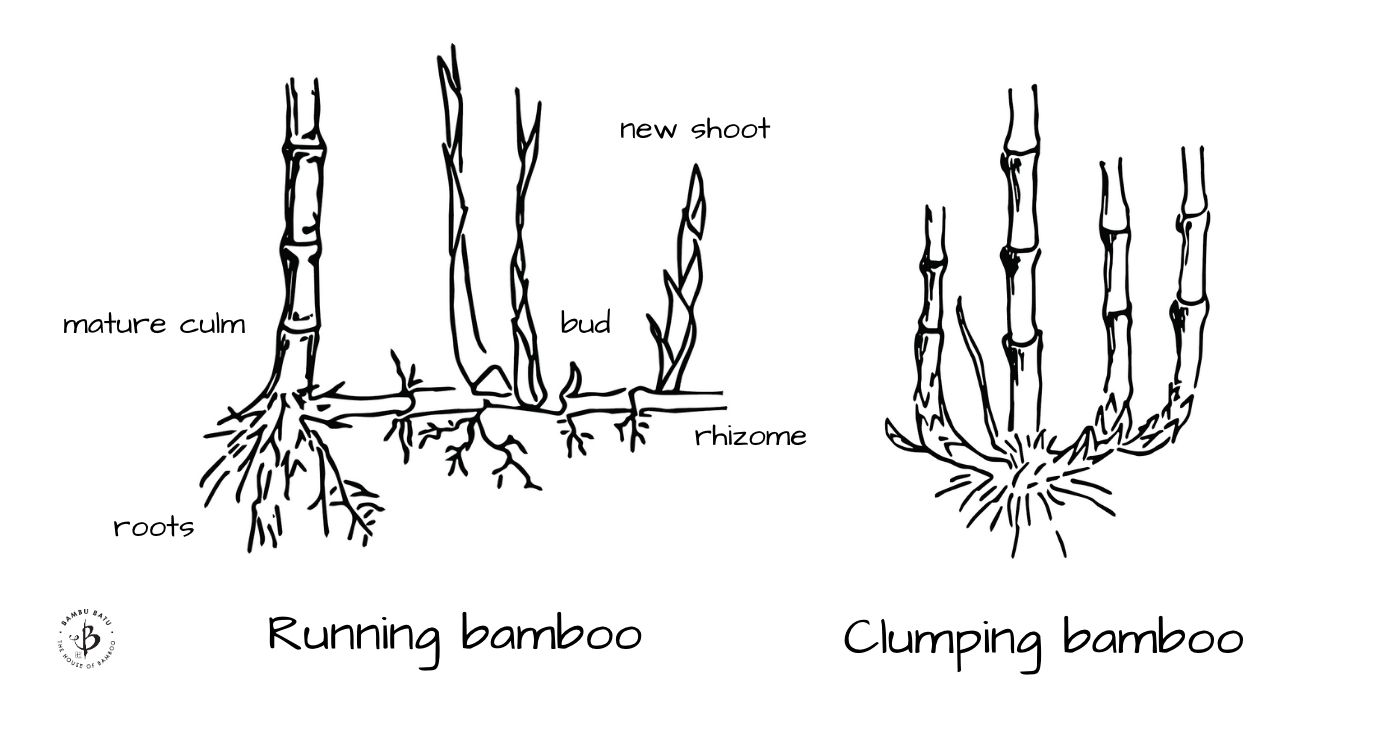

The first thing to understand is that you can basically divide bamboo into two different categories: running bamboo and clumping bamboo. As you might guess from the name, running bamboo can spread quickly and cover great areas, basically running amok. These are the varieties you need to be careful with. But not all varieties of running bamboo are created equal. Some species are especially aggressive and invasive, and those are the ones we want to warn you about.

Clumping bamboos, by contrast, tend to stay put. They have a different type of root system that remains tight and compact. Generally, each species of clumping bamboo has its maximum footprint. In other words, once the grove reaches full size, which could be anywhere from a few feet to several yards in diameter, it will stop spreading. There are hundreds of kinds of clumping bamboo, including some very popular and attractive varieties like Oldhamii and Buddha’s Belly, of the genus Bambusa.

Even some kinds of clumping bamboo can get out of control if they are left to their own devices. While most clumps will reach maximum size and then stop spreading, there are also open-clump species which will continue to spread over time, albeit slowly.

Where they grow

Generally speaking, running bamboos and clumping bamboos prefer different types of climates. This is not a hard and fast rule, but it is an important distinction to be aware of. Most of the clumping bamboos are native to tropical and subtropical climates like South East Asian and Indonesia. This makes many of those varieties difficult to grow in most parts of Europe and North America. But again, there are a number of exceptions.

If you live in a cooler, more moderate climate, you’ll probably have better luck growing running bamboo, which is typically native to temperate climates like central and southern China. These varieties are much hardier in the winter, able to tolerate freezing temperatures for longer periods of time. This makes running bamboo more popular in many parts of the U.S.

How running bamboo becomes a problem

The problem is, once a running bamboo gets going, it can be almost impossible to stop. Usually someone will start out with a couple pots and gloat over how well they are growing. But when the spreading doesn’t stop, the bamboo easily becomes a nuisance.

There’s an old saying about bamboo: The first year it sleeps, the second year it creeps, and the third year it leaps. The point is that you might not notice anything out of the ordinary in the first year or two of growing bamboo. But underground, the vigorous rhizome root system is gaining a foothold. And once the foundation is in place, that’s when you really see the new shoots coming up around the yard.

If not well contained, the bamboo shoots could show up in your flower beds, your vegetable patch, or your well-manicured lawn. Not only that, but they have no respect for property lines. Bamboo frequently crawls under fences and wreaks havoc on other people’s gardens. This is not a good way to keep on good terms with your neighbors.

Notorious runners to watch out for

There are hundreds of varieties of running bamboo out there, but many of the most aggressive species belong to the genus Phyllostachys.

- Phyllostachys aurea (Golden bamboo or Fishpole bamboo): An attractive, fast-growing species that gets up to 30 feet tall with thick culms and dense green foliage, Golden Bamboo has become a very popular variety. It’s especially popular for privacy screens on account of its height and density. It’s actually a great choice in cold climates where it’s less likely to spread out of control. But beware, with ample water and mild winters, it can spread like crazy. (Not to be confused with Bambusa vulgaris, an open-clump variety of timber bamboo which is also known as Golden Bamboo.)

- Phyllostachys aureosulcata (Yellow groove bamboo): Widely grown as an ornamental, this species has a distinctive yellow stripe that runs along the culm grooves. Shoots can grow up to 50 feet tall and 2-3 inches in diameter. The fresh shoots are also known to be quite tasty. Some New England states have banned this species, which is cold-hardy and invasive.

- Phyllostachys bissetii: Very cold hardy with a vigorous growth habit, Bissetii is a popular choice for privacy screens. In the coldest parts of the country, it usually gets about 10 feet tall. In more moderate areas, like USDA zone 7, it can exceed 30 feet in height with an aggressive root system.

- Phyllostachys rubromarginata: Another popular choice for privacy screens, because it fills in so quickly. It’s not quite a timber bamboo, but it’s larger than most, with culms up to 30-40′ tall and 3″ thick. A reddish hue on the new shoots has earned it the nickname Red margin bamboo.

Have you run into another extremely invasive species of bamboo that we overlooked? Please let us know about it in the comments section!

Recognizing and identifying running bamboo

A tricky thing about bamboo is that it comes in over a thousand varieties, many of which look extremely similar, almost indistinguishable to the untrained eye. In fact, it’s not uncommon for nurseries to mislabel their bamboo. (That’s why we always recommend finding a nursery that specializes in bamboo.) There can be a lot of confusion with the common names, such as Golden Bamboo, which could actually refer to a few different species. Then there are names like Timber Bamboo, which don’t tell you anything about the species, only that it gets real big.

But there is a way to identify Phyllostachys, which is the largest genus of running bamboo, including dozens of species. If you look closely at the stems (culms) of a Phyllostachys bamboo, you’ll see a sulcus groove that runs lengthwise between the nodes. The grooves alternate sides, from one internode to the next. It’s a distinctive characteristic, and you’ve probably noticed it before, because Phyllostachys are so common and prolific.

If you see this groove, you can be sure that you’re dealing with a running bamboo. And for a novice, that’s a pretty good start. It won’t tell you if it’s a super-aggressive runner, but you’ll know that it’s a runner. Unfortunately, if you don’t see the groove, you can’t be certain that it’s a clumping bamboo. You’re only pretty sure it’s not a Phyllostachys. Yeah, nobody said this would be easy.

Why do people plant running bamboo?

Though it may sound like madness to anyone who has ever been sued by their neighbor or had to pay a few thousand dollars to remove a running bamboo grove, there are actually a few reasons people might choose to plant a running variety.

- Fast-growing: Sometimes you just want to plant something that will fill an area quickly, without waiting 2 or 3 years. This is often the case with a privacy hedge, for example.

- Cold-hardy: In general, running bamboo can better tolerate cold weather and deep freezes in the winter.

- Inexpensive: Runners are less expensive at the nursery, because they propagate so easily. But a big price could come later on if the bamboo invades your neighbor’s antique rose garden or tears up an underground utility line.

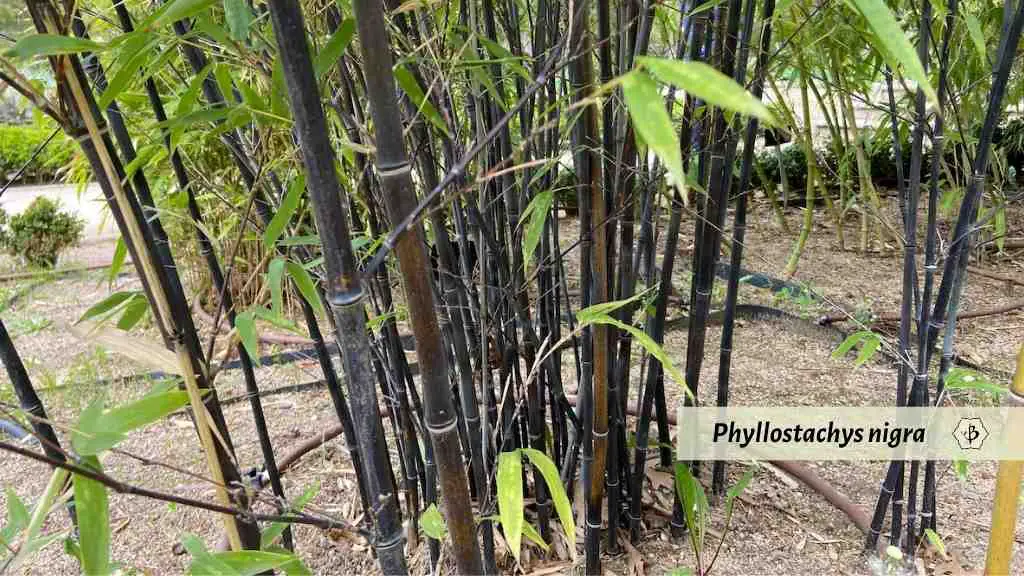

- Attractive species: Some of the very attractive and desirable bamboo species happen to be runners, like Black Bamboo (Phyllostachys nigra).

Invasive bamboo with a low profile

Some of the smallest varieties of bamboo, from the genus Pleioblastus and genus Sasa, for example, can also become rather invasive. The stems of dwarf bamboo are short and delicate, but their roots are aggressive and tenacious.

On the other hand, the rhizomes of these petit bamboo varieties are more shallow and fragile. Consequently, it is far easier to dig out unwanted patches of dwarf bamboo or contain them with some manner of root barrier. Beware, however, that unless the small bamboo is thoroughly removed, it will certainly grow back. And once the roots pass under a fence line, they will have the chance to become a nuisance in your neighbor’s garden.

Can clumping bamboo be invasive?

Clumping bamboo is generally synonymous with non-invasive bamboo. The rhizomatous roots have a different shape and growth habit, so the plants manage to contain themselves without spreading too far. But there are other ways of becoming invasive.

Bambusa vulgaris is a tropical, clumping bamboo species from the Far East that now covers tropical regions throughout the globe. Although its roots are not running and it hardly ever flowers or produces seeds, the stems and branches are exceptionally vigorous. If a small piece falls to the ground, it will invariably sprout roots and establish itself as an independent, new plant. From India to Angola to Puerto Rico, you can now find various strains of Bambusa vulgaris encroaching on native, tropical habitats all around the world.

To make matters worse, these far-flung corners of the world lack the bamboo culture of Asia, and so the plant has much less value or status in these regions. Therefore, many view it as nothing more than a fast-growing nuisance. Only in recent years have people in Latin America and West Africa come to recognize bamboo’s usefulness for things like building and charcoal production.

How B. vulgaris traveled from China to Africa and the Americas is another mystery. The prevailing theory is that the Spanish explorers of the 17th and 18th centuries carried bamboo from China to their new settlements for erosion control around rivers and waterways. There is scant evidence that the Spanish conquistadors were using bamboo for construction or weaving.

Control your bamboo

Because of its invasive potential, some cities and homeowner’s associations actually have laws and regulations against planting bamboo. For the safety of your garden and your neighbors, we always recommend using a root barrier when planting a running bamboo species.

Bamboo Shield makes an excellent root barrier product, available for purchase on Amazon. The barrier, available from Amazon, comes in three sizes, for cold warm, and tropical climates. The warmer the climate, the thicker the barrier.

Further reading

If you found this article on invasive bamboos helpful, please consider subscribing to our blog. You might also enjoy some of these other articles.

- Introducing bamboo: Genus by genus

- Is bamboo invasive or just expansive?

- How to get rid of bamboo

- Tips for bamboo containment and removal

- 15 Varieties of Cold Hardy Bamboo

- Proverbs about bamboo

- Pros and Cons of Potted Bamboo

- Great bamboo nurseries of America

FEATURED PHOTO: A running bamboo rhizome spreads across the asphalt. Photo by Fred Hornaday.

How can I find out if my bamboo is Golden bamboo ?

Here’s a video about golden bamboo identification that might help:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MvIw-cTtpTw