When you go looking for attractive, ornamental bamboo, you’ll eventually see images or hear mention of Tortoise Shell Bamboo. Even the name has an irresistibly exotic allure. Indeed, it’s one of the most interesting varieties of bamboo to look at. And while it may not be the easiest bamboo to find or to cultivate, neither is it the most difficult.

The common name Tortoise Shell Bamboo refers to Phyllostachys edulis ‘Heterocycla’, a subspecies of the supremely important Moso bamboo. Moso, or Phyllostachys edulis, is the timber variety grown for bamboo clothing, bamboo flooring, and a host of other commercial uses. The cultivar ‘Heterocycla’ isn’t nearly as important economically, due to the strange and uneven shape of its culms. But this odd pattern makes for a beautiful specimen plant, and a dazzling addition to any bamboo collector’s garden.

NOTE: This article first appeared in December 2020, last updated in February 2024.

What is Phyllostachys edulis?

Phyllostachys is one of the most widespread genera of bamboo, chiefly native to China, but also Japan, Taiwan and Vietnam. The genus includes a great diversity of temperate bamboos, from small specimens ideal for bonsai (P. aurea ‘Waminita’), to massive timber varieties best suited for building and construction (P. bambusoides).

Their running rhizomes also make Phyllostachys one of the most vigorous and fastest-spreading groups of bamboo. This can be a desirable characteristic for some gardeners, those looking for a plant that will fill in quickly. But others may find them to be something of a menace, taking over the garden and displacing other natives and ornamentals.

Phyllostachys is probably the most common genus of bamboo in temperate climates, including much of North America. Most species are cold hardy down to around 0º F. Their rapid growth rate and dense foliage make them great candidates for privacy hedges.

Growth habit of Phyllostachys edulis vs P. edulis ‘Heterocycla’

The Moso species

Formerly classified as P. pubescens, but commonly known as Moso bamboo, this species grows wildly and in cultivation in large areas of central China. P. edulis is the most massive member of the genus, sometimes exceeding 100 feet in height, and 4 to 5 inches in diameter.

Outside of China, P. edulis does not perform nearly as well. But farmers in Florida and the deep south have attempted to grow Moso commercially, with mixed results. A temperate variety, hardy down to 5º or 10º F, Moso can grow in zones 6-9. But it really does best in zones 7 and 8, and only east of the Mississippi. Still, it won’t usually get more than 50 feet tall. Gardeners in the US tend to have more success with P. bambusoides, or Japanese Timber Bamboo, which is more temperate and has very thick culm walls.

Subspecies ‘Heterocycla’

Phyllostachys edulis ‘Heterocycla’, Tortoise Shell Bamboo, prefers a somewhat warmer climate, including zones 7-10. It also prefers more humidity and moist but well-drained soil. In the eastern US, they only get about 15 to 25 feet high. The species is generally available from bamboo nurseries and growers in the southeast, but the “Heterocycla’ cultivar remains fairly rare. You’ll definitely need to go through a specialist in order to find one of these.

Though they are hard to find and fairly particular about their growing conditions, the Tortoise Shell Bamboo remains a very highly sought-after variety. As you can see from the photos, their culms are most unusual and strikingly beautiful. Young culms come up grayish in color, and slowly turn a yellow-green with age. Eventually, they take on an almost orange hue, as shown in the pictures below. Young culms also have a fuzzy texture which adds yet another interesting dimension to the plant.

The most striking feature, however, is the compression between the nodes. P. edulis naturally has relatively short internodes, particularly near the base of the plant. But the ‘Heterocycla’ internodes are slanted and closely compressed on alternating sides of the culms, resulting in a zigzag pattern similar to a tortoise shell. In Japan, they call it ‘Kikko’, which literally means tortoise shell.

This tortoiseshell pattern can sometimes appear on other varieties of Phyllostachys, especially on the lowest nodes near the base. But it occurs rarely and sporadically. Heterocycla specimens display this feature with consistency.

Other cultivars of P. edulis

In addition to the Phyllostachys edulis ‘Heterocycla’, aka Tortoise Shell Bamboo, the species has a number of other known cultivars, or subspecies.

- Phyllostachys edulis ‘Bicolor’: Buttery yellow with thick green stripes on alternating sides of the stems. Smaller in size and less cold tolerant than the original species, this is a rare and difficult variety to grow, but remarkably rewarding as well.

- Phyllostachys edulis ‘Subconvexa’: An especially rare variety with even more tightly compressed nodes, still in the tortoiseshell pattern. Grows about 20-30 feet tall in China and Japan.

- Phyllostachys edulis ‘Nabeshimana’: Also called ‘Tao Kiang’, this exotic cultivar produces some of the most exquisite colorations of any bamboo, with yellow and green candy-cane stripes running up and down the culms.

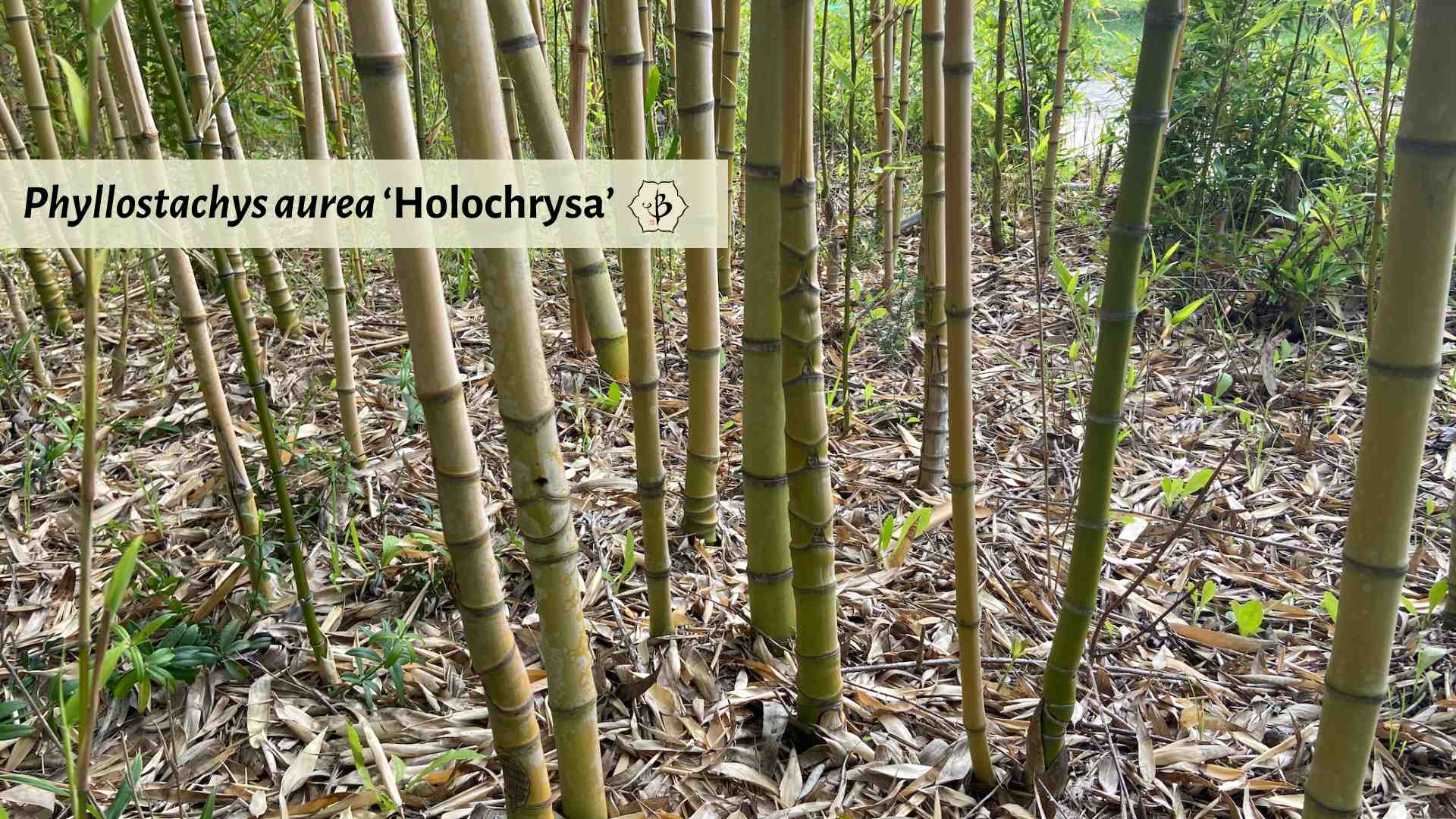

Other examples of the Tortoise Shell effect: Phyllostachys aurea

The tortoiseshell effect is striking and exceptional, and yet P. edulis Heterocycla is not the only bamboo cultivar to exhibit this characteristic. It’s not uncommon for Phyllostachys aurea, a very common ornamental species, to display this trait. But it tends to appear only on select poles and only very near the base.

But there’s a subspecies of P. aurea called Holochrysa which expresses this morphological irregularity much more often. This species is considerably smaller than Moso bamboo, in both height and girth. These distinctive features can add great interest to a collector’s garden, especially when the lower branches are well pruned to expose the culms, and the unusual poles lend themselves to a variety of craft applications.

The importance of Moso bamboo

In addition to its impressive stature, Moso is perhaps the most economically important bamboo species of all. Moso bamboo is the raw material species for all bamboo clothing and textiles, as well as all bamboo flooring, and most of the pressed bamboo kitchenwares on the market today. It grows naturally in thick forests in central China, but farmers now cultivate large swaths of Moso for commercial use.

You’ll be happy to know that China’s giant panda does not subsist on Moso. Therefore, the commercial harvesting of Moso does not pose a threat to this precious and threatened animal species. Furthermore, Moso is one of the fastest-growing bamboo species of all, with new culms sprouting up at a pace of three feet a day. It is the largest of all the temperate bamboo species. (Tropical varieties, such as Dendrocalamus and Guadua can grow taller and thicker.) Renewing itself the way grasses do, Moso can be harvested continually without the need for replanting, like any variety of bamboo.

Finally, as the name might indicate, P.edulis is one of the more popular species of edible bamboo. Check out our in-depth article on Eating Bamboo, to learn more about this ancient and abundant source of nutrition.

Further reading

If you’d like to learn more about bamboo cultivation and speciation, take a look at some of our most popular articles.

- Introducing bamboo: Genus by genus

- Buddha Belly: Bamboo of the highest calling

- Oldhamii: The most popular species of bamboo

- Best bamboo varieties for your garden

- Shopping for live bamboo plants

- Bamboo anatomy: 9 parts of the bamboo plant

Great infomation!!

Thank you 🧐🙏