It’s easy to fall in love with bamboo. It’s a beautiful plant with tall, elegant canes and thick, leafy greenery. Bamboo has a rich history and thousands of uses. But many gardeners have come to dread bamboo, because some varieties will spread out of control and take over the whole garden, becoming almost impossible to remove. That’s why the more experienced gardeners choose to plant clumping bamboo. Clumping bamboos offer all the grandeur of a noble grass without the nuisance of an invasive species.

There is an abundance of clumping bamboo species that provide beauty without the risk of overtaking your neighborhood with invasive grass. Typically, clumping bamboos tend to come from tropical and subtropical climates. Conversely, running bamboo generally does better in more temperate climates. But this is not a hard and fast rule. You can also find a handful of cold-hardy bamboo species that are non-invasive but will survive the frost of winter.

The following article includes about 15 popular species of clumping bamboo. For additional ideas, check out our newer blog post: 10 More clumping bamboo species. And if you prefer videos, check out my explanation of Running Bamboo vs Clumping Bamboo on YouTube.

NOTE: This article first appeared in July 2020, most recently updated in May 2024.

| Bamboo genus | Description |

| Bambusa | Subtropical clumpers that come in an enormous variety and tolerate limited freezing |

| Borinda | Cold-hardy clumpers native to the Himalayas |

| Chusquea | Neotropical genus notable for the solid, or nearly solid, rather than hollow, culms |

| Dendrocalamus | Tropical giants from Southeast Asia, suitable in zones 9 and up |

| Fargesia | The most cold-hardy genus of clumping bamboo |

| Guadua | Tropical giants of Central and South America, suitable in zones 9 and up |

| Himalayacalamus | An Asian genus native to the lower elevations of the Himalayas |

| Otatea | Drought-tolerant clumpers native to Mexico, Central America, and Colombia |

Choose a clumper and stop the spread

Before deciding what sort of bamboo to plant, it’s important to understand a few of the basic fundamentals about bamboo gardening.

Q: Is it possible to plant bamboo and beautify your garden without the bamboo running out of control and becoming invasive?

A: Yes! If you plant a clumping type of bamboo, you will have a much easier time keeping it contained.

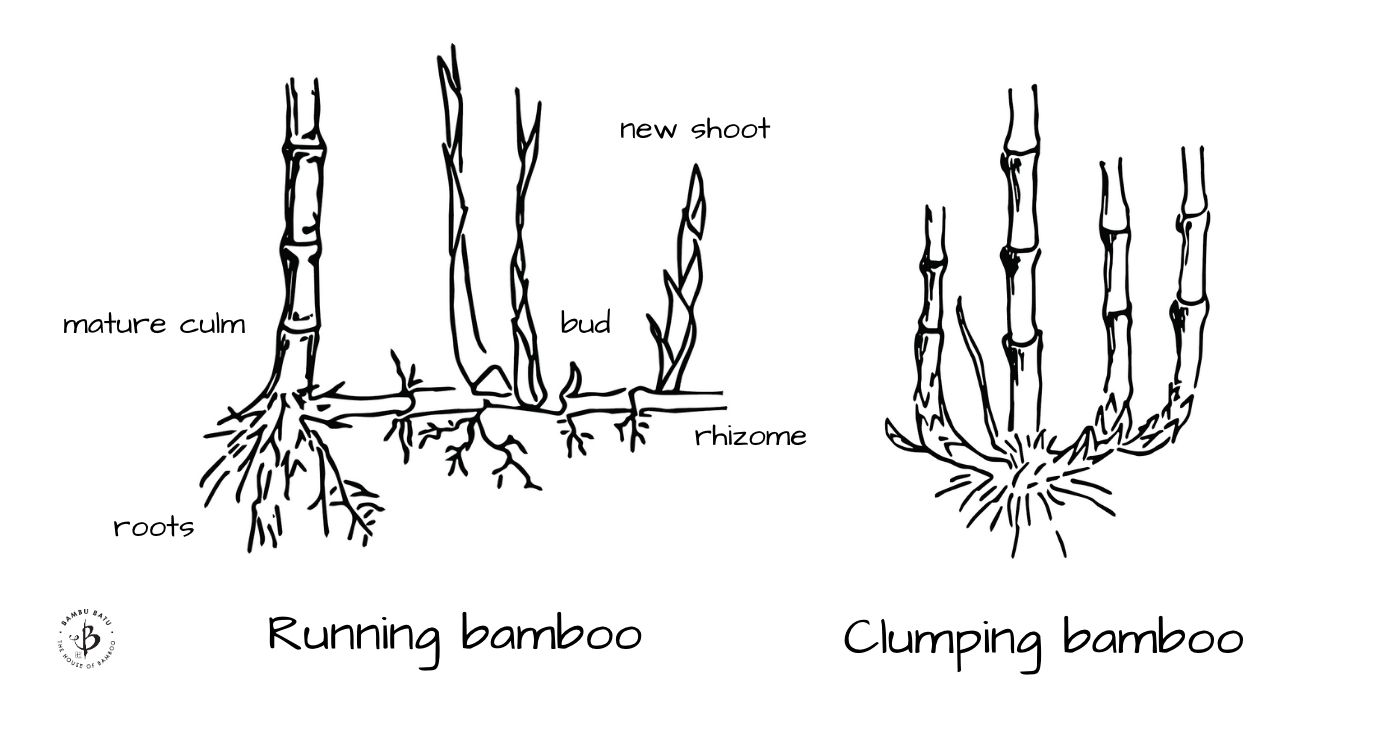

Q: What’s the difference between running bamboo and clumping bamboo?

A: There are more than a thousand known varieties of bamboo, but we can lump them into two basic categories. Running bamboos have leptomorph or monopodial rhizome roots, which continue to spread and easily become invasive. Clumping bamboos have a much more compact root system, with pachymorph or sympodial rhizomes. These U-shaped rhizomes tend to grow upward instead of outward, resulting in a well-contained and non-invasive bamboo plant.

Read more about the dangers of planting running bamboo in these articles:

- Running bamboos: Why must you run?

- Notorious runners: The most invasive varieties to watch out for

- Is bamboo illegal?

- Running Bamboo vs Clumping Bamboo on YouTube

Q: How big will a clumping bamboo get?

A: The size of a clumping bamboo can vary greatly. Although compact by bamboo standards, a mature grove of clumping bamboo will be at least 3 or 4 feet in diameter, and could grow to 15 or 20 feet wide. Some varieties of clumping bamboo grow faster and spread large than others. These fast-growing clumpers have pachymorphic rhizomes, but rather than just an inch or two, they can grow over a foot long. We call these open clumpers, and they will require a bit more maintenance.

In any case, it’s still important to maintain a clumping bamboo, inspecting the roots and cutting back old culms. But a clumping bamboo will require far less maintenance than a running bamboo. To keep a clumping bamboo more compact, it’s relatively easy to remove the outermost canes. Just cut them down to the ground with pruners or a saw.

Selecting a clumping bamboo variety for your garden

As you can see, there are many advantages to planting clumpers instead of runners. But keep in mind, there are times when it might make more sense to plant a runner. If you want a fast-growing bamboo to fill in a privacy hedge, for example, a running bamboo will work better. Or if you need a cold-hardy bamboo, runners are usually a better choice. Most clumpers are not very cold-hardy, with the exception of Fargesia.

Now that you’ve decided to plant a clumping variety, it’s time to look at the best choices of bamboo genera and species.

BAMBUSA

One of the most diverse genera of bamboo, Bambusa includes some of the most attractive and appealing species. And rest assured, every member of this genus is a clumping variety.

Bambusa oldhamii: Oldham’s, as it is commonly known, is one of the most popular species of bamboo in North America. This towering timber bamboo can easily reach 50 feet high in ideal conditions with a good water supply. With long, straight poles that can get up to about 4 inches in diameter, it can be useful for all sorts of crafts and construction projects. The plant will typically spread to about 10 or 15 feet across, so allow it some space. But fear not, it won’t take over like Vivax, or one of those super aggressive varieties of Phyllostachys.

B. guangxiensis: This clumping bamboo is called “Chinese Dwarf,” but it can actually grow up to 20 or 30 feet tall. It’s a very attractive species and easy to keep contained. The foliage on this bamboo is especially thick and bushy, so it makes a pretty good privacy hedge compared to other clumpers. It prefers warmer, subtropical climates and will not tolerate freezing weather.

B. textilis: Weaver’s Bamboo, along with the subspecies ‘Gracilis’ (Graceful Bamboo), is one of the most popular varieties of bamboo. The clumps are unusually dense and compact, so need to worry about them taking over the yard. At the same time, the culms are very tall, often 30 to 40 feet high with a gentle arch near the top. And compared to other subtropical clumping bamboo, B. textilis and its various subspecies are quite tolerant of the cold, hardy down to about 10-12º F.

Bambusa ventricosa: Another favorite among bamboo lovers, Buddha Belly has some of the most interesting and attractive culm structures of any bamboo. Available in a number of cultivars that range from Giant Buddha Belly (Bambusa Vulgaris cv. Wamin) to Dwarf Buddha Belly, it’s practically a must-have for any serious bamboo collector. This plant earned its name from the bulbous internodes of its culms. The unusual shape makes it a great centerpiece for an Asian-style garden. The giant variety can get up to about 45 feet tall and 15 feet wide. But the dwarf variety is of course more compact. It can even be contained in a small pot and grown like a bonsai with dazzling results.

Other popular Bambusas include Alphonse Karr, a beautifully striped bamboo, and Bambusa multiplex “Tiny fern”, a dwarf variety that only grows a couple of feet tall.

BORINDA

This is an unusual genus of clumping bamboo with just eight species. Until recently, members of Borinda were classified as either Fargesia or Yushania. Native to the Himalayan regions of Bhutan, Nepal and southern China, these are generally a cold-hardy, shade-tolerant, and very decorative assortment of bamboo.

Some of the most interesting and attractive species of Borinda include B. fungosa, also called “Chocolate Bamboo”, a weeping variety with deep brown culms, and B. papyrifera with its powdery blue culms. B. boliana is one of the largest bamboos in this genus, growing 20-30 feet tall, with gracefully arching culms.

Most Borinda species prefer cooler climates, and about a half-day of sun. They are generally cold-hardy down to around 10º F. Not recommended for hot, southern climates.

CHUSQUEA

Native to the higher elevations of Latin America, this genus tends to be more cold-tolerant than most other clumping varieties. But its most distinguishing characteristic are the solid, or nearly solid, culms. Rather than the typically hollow stems of other bamboo, these poles will be even stronger and less prone to cracking.

Chusquea gigantea: The largest member of the genus, this species can grow 15-25 tall. About 1.5 inches in diameter, the attractive culms are primarily yellow in color, but dark green around the nodes, producing a very interesting effect.

FARGESIA

Most kinds of clumping bamboo are native to the warmer and more tropical climates. If you’re looking for a clumper that can withstand deep freezes in the winter, your best bet is probably something from the genus Fargesia.

F. dracocephala: “Dragon head bamboo” has thick culms growing to about 10 feet, with a thick, weeping leaf canopy that can provide a good privacy hedge. Not recommended for hot, humid climates, but cold hardy down to -10º F.

F. murielae: Commonly known as “umbrella bamboo”, many consider this to be among the most beautiful varieties for cultivation. New shoots have a light blue hue, turning dark green and yellow with age. Growing this bamboo in a shady area will help preserve the rich blue shade. Thin shoots will get about 12 feet tall, and it’s hardy down to -20º F.

F. nitida: “Blue fountain bamboo” earned its name from the dark purple, bluish culms and the thick, cascading canopy of foliage. One-inch poles can get to about 15 feet tall, and thrive in temperatures as low as -20º F.

F. rufa: A compact, thick and bushy variety, Rufa much prefers the cooler climates, and also does well in partial shade, protected from afternoon sun. This species is hardy down to -15º F. Thin culms grow to about 10 feet tall.

F. scabrida: Another colorful variety, with shoots that come in shades of orange, blue and purple, eventually turning deep green. Also known as the “Asian Wonder,” it grows well in sun or shade, and is hardy to -10º F. Mature plants get 10 or 15 feet tall, with culms less than an inch in diameter. Although it’s a clumper, it does have a more vigorous growth habit, making it a popular choice for many gardeners, but a point of concern for others.

Fargesia sp. ‘Jiuzhaigou’: This species includes many interesting and cold-hardy cultivars, including “red dragon” and “black cherry”. As the names suggest, these are some more colorful varietals. With thin culms growing to around 10 feet, this is a more compact species of bamboo, but cold hardy down to -20º F.

HIMALAYACALAMUS

Native to the lower elevations of the Himalayas, these clumping varieties originally come from Bhutan, China, Tibet, India, and Nepal. They are relatively cold-hardy as far as clumping bamboos go.

Himalayacalamus hookerianus (Himalayan Blue): The richly colored, powdery blue culms give this bamboo an especially pleasing appearance. It prefers warmer weather, but can withstand cold winters, and also grows well around ponds and in containers. Culinary tip: fresh shoots of the Himalayan Blue are edible and are said to be quite tasty.

OTATEA

This is one of the most widespread genera of bamboo to come out of Mexico. The name of this genus comes from the Nahuatl word “otatl”, meaning bamboo.

Otatea acuminata (Mexican Weeping Bamboo): A versatile species, this bamboo does well in a range of conditions. Near the ocean, it’s not bothered by the salty sea spray. In California, it can tolerate the dryness. It’s native to Northern Mexico, after all. But it’s also cold hardy down to about 20º F. And in small gardens, the weeping bamboo does quite well in a pot. The thin poles grow up to 10 or 15 feet tall, but the gracefully cascading leaves are what give the plant its unique appeal. It also has a dwarf variety, in case you’re looking for something especially compact.

Tropical bamboo

Some of the most impressive clumping bamboos come from Central America and Southeast Asia, but they are difficult to grow successfully in the U.S. But if you live in a tropical or subtropical zone like Southern Florida, you can try growing a wider selection of Bambusa or Dendrocalamus. In the right climate, D. giganteus, D. sinicus and D. validus can provide amazing specimen plants and produce tremendous culms for building and construction.

Guadua angustofolia is extremely important in Central and South America, especially Colombia, but it’s difficult to grow in the states. Some other interesting genera of tropical bamboo, best in zones 9 and up, are Gigantochloa, Schizostachyum and Thyrsostachys.

More slow-spreading bamboo

In addition to the popular genera of clumping bamboo listed above, there are a few more options for those who fear being overrun by vigorous grass. Some bamboos just don’t grow very big. While other species can exceed 100 feet in height, others don’t grow any larger than a pencil. Naturally, the smaller they are, the easier they will be to keep in check.

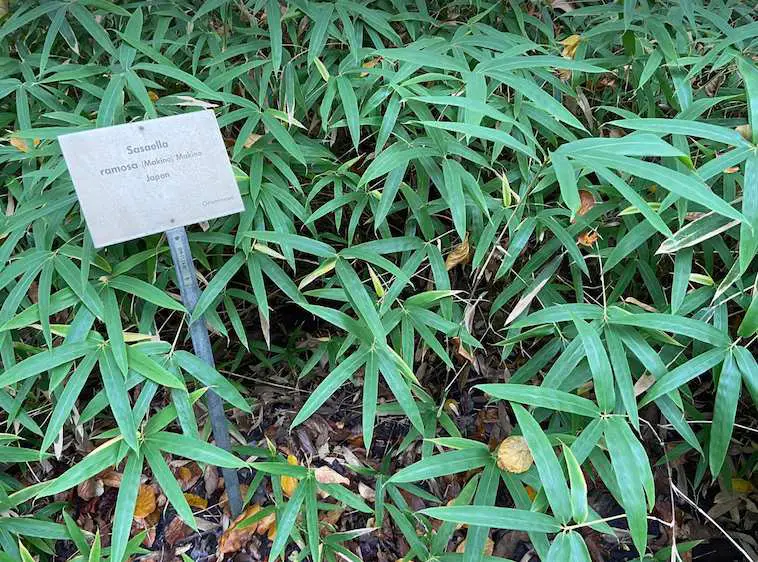

We’ve written a complete article about dwarf bamboo and ground covers. Most of the dwarf varieties are runners, such as Pleioblastus fortunei “Dwarf whitestripe”, Pseudosasa owatarii, and many species belonging to the genus Sasa. But even though they are runners, the culms are short and thin, and fairly easy to cut back. It is essential, however, that you remember to cut them back and inspect the roots on a regular basis. That means at least once a year in a cold climate, or twice a year in a warmer climate.

Clumping dwarf species like Bambusa multiplex “Tiny fern” and “Tiny fern striped” will be even easier to confine to a limited area.

Containing and maintaining bamboo

Now, just because you’ve planted a clumping variety instead of a runner, it doesn’t mean that your work is done. Every garden requires some maintenance, and that’s just as true for a clumping bamboo. It certainly doesn’t require the same degree of relentless defense as running bamboo, but regular pruning is important.

It’s easy to forget about dwarf bamboo because it seems so small and innocuous. But the roots are always far more active than the visible vegetation will let on. One method of containment is to dig a trench around the area in which you’d like the bamboo to remain. This makes it easy to see when the roots are beginning to overreach their boundary.

With big clumpers like B. Oldhamii and D. Giganteus, the plant can occupy a pretty large footprint. If you don’t want something that’s going to spread 15 feet wide, you’ll want to select a small or medium-sized species.

Cutting back the new shoots as they slowly spread is usually enough to keep a clumping bamboo in check. One of the best ways to do this is by digging a trench around the plant’s perimeter.

Further reading

If you found this article useful, please consider sharing it and subscribing to our mailing list. You might also enjoy some of the following blog posts.

- 10 Best bamboo varieties for your garden

- Growing bamboo: The complete how-to guide

- How to get rid of bamboo: Remove the menace

- The best bamboo varieties for construction

- Bamboo containment

PHOTO CREDIT: A constellation of clumping bamboo at the Bambouseraie in southern France. Photo by Fred Hornaday.

Excellent

Very interesting and informative 👍