When it comes to bamboo trivia, few questions are more frequently asked or more inconclusively debated. How many bamboo species are there?

Most authors and experts agree that there are approximately 1,500 species of bamboo. Occasionally, you may come across a claim with an extremely precise number, like 1,662 known species, or 1,718. But I put little faith in such exact figures. In truth, it’s not possible to count the exact numbers. Furthermore, there is a large and indefinite number of bamboo sub-species, or cultivars, which brings the total sum closer to 2,000.

If you want to go out counting bamboo species on your own, you probably won’t get too far. Visit the most expansive bamboo nurseries in Florida or Tennessee, and you’re unlikely to see more than 100 species in their collections. The lion’s share of varieties on that long list of 2,000 are rare and exotic specimens that might only be found in the deepest jungles of Central America or Latin America. To seriously tour the vast world of bamboo diversity, you’ll need to fetch your pith helmet and renew your passport.

Check out our directory of bamboo species for a comprehensive reference filled with links and photos.

NOTE: This article first appeared in March 2023, most recently updated in May 2025.

Counting bamboo species

Counting the total number of bamboo species in the natural world is a bit like counting the stars in the Milky Way or the angels on the head of a pin. For one thing, the number is impossibly too large to grasp. More importantly, the notion of speciation is a manmade classification without black-and-white delineation. Bamboo has been proliferating and evolving for thousands of years, and it is especially abundant in the tropical zones near the equator. Surveying these jungles is physically challenging. But the real challenge is to discern between intra- and inter-species differentiation.

Like you and me, every member of a given species has some degree of uniqueness. That’s called phenotypic variation. As populations spread out, they will continue to evolve and differentiate. Eventually, a new branch forms in the evolutionary tree, and you have a new species. But the thing about the evolutionary tree, it’s just a metaphor. You can’t actually hold a branch in your hand and say, “Here we have it, a new species!”

To make matters even more ambiguous, we also have bamboo cultivars or subspecies. When a botanist discovers a new variation, and can’t make up her mind whether it’s a new species or not, we have the comforting but ambivalent option to label it a subspecies. But one botanist’s cultivar could easily be another author’s brand-new branch on the tree.

Discrepancies in bamboo classification

As bamboo awareness continues to increase, and plants and plant-lovers alike migrate around the world, the struggle to arrive at a standard system of naming and classification has intensified. From region to region, even island to island, bamboo species have their own local names. The same species of bamboo might be found in a different region but under a different moniker, and conversely, a similar common name could refer to an entirely different species.

At the same time, scientists and specialists go traveling the world, collecting more and more data. As the knowledge base expands, plants that were once held to be closely related can be re-classified into more separate categories. And, naturally, the opposite can also happen.

Sometimes a genus of bamboo will be broadened, as formerly unrelated specimens are consolidated together. In other cases, a genus gets reduced, while certain members get relisted elsewhere. It’s important to remember that Mother Nature does not draw clean lines between species and genera. These taxonomical groupings are completely manmade tools of convenience to help us find our way through the murkiness of the natural world.

Categorizing bamboo

Botanists and plant scientists define bamboo as a subfamily, Bambusoideae, within the grass family, Poaceae. And before we get to the genus or the species, which typically follow after the family, the bamboo subfamily is divided into three tribes.

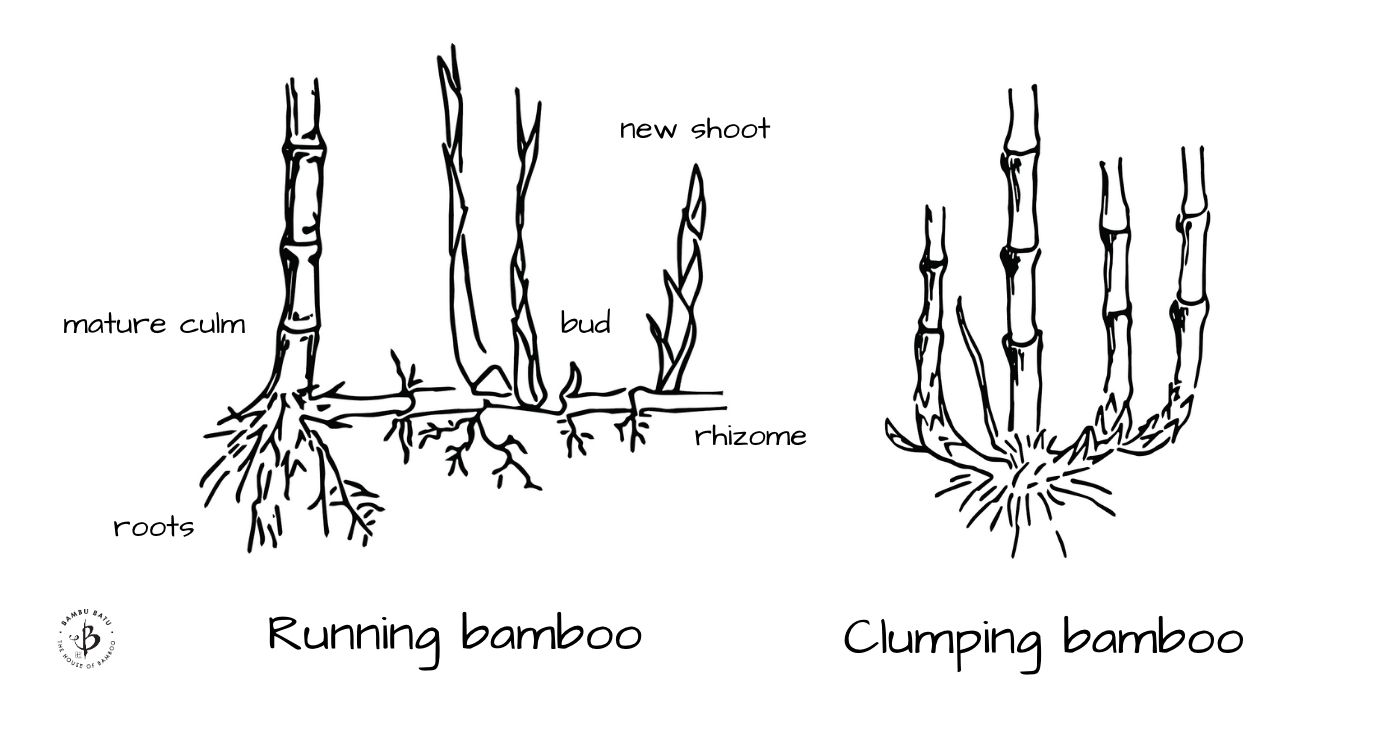

Most people with any knowledge of bamboo are familiar with runners and clumpers, which make up the first two tribes of woody bamboo. A third tribe, known as Olyreae, consists of herbaceous or non-woody bamboo, soft, low-growing and primarily found in the shady understory of the Amazon rainforest.

But even though we can divide the many species of bamboo into temperate runners and tropical clumpers, it’s not always a perfectly clear distinction. Botanically speaking, bamboo has two types of rhizome systems, either pachymorph (clumping) or leptomorph (running). But some running types run pretty slowly. And some clumping bamboo tends to spread out; we call those open clumpers.

If experts – and nature herself – can’t even agree on this fundamental distinction, you can imagine how hard it will be to draw sharp lines between the species.

Examples of blurry bamboo distinctions

Among the 90 to 115 genera of bamboo (another debatable number), several have seen significant renaming and reordering in the last couple of decades. There are also a handful of bamboo species that have large numbers of cultivars, as well as diverse species that have not been subdivided.

Genus Arundinaria

The genus Arundinaria provides a perfect example of how bamboo classifications change and evolve. Today there are three species of running bamboo, all native to North America, which officially belong to this genus. In other words, the great majority of authors recognize only those three species as true Arundinarias.

In former times, however, this genus had as many as 400 species. The preponderance of those bamboos were eventually reclassified into different genera, including Bashania, Fargesia, Sasa, and others. These other genera all comprise temperate, cold-hardy bamboo. Oddly though, they are not all runners. Bashania and Fargesia make up some of the more unusual bamboo varieties which are temperate but clumping.

The geographic distribution of Arundianria is unique. These are the only three species of bamboo native to the contiguous United States. But in the older systems, Arundianria was spread all across Asia and even Africa.

Genus Fargesia

While the genus Arundinaria was reduced to a perfect trio, Fargesia has had a very different history. By some measures, this odd collection includes more than 80 species of atypically cold-tolerant clumpers. They are primarily native to the slopes of the Himalayas, where they’ve adapted to the extreme climate. Other species are native to China and Vietnam.

For their cold-hardiness, Fargesia belongs to the tribe Arundinaceae. However, some experts would consider bamboos like these, as well as Borinda and Thamnocalamus, as tropical bamboo of the tribe Bambuseae.

When bamboo varieties manage to defy the basic boundaries of classification, what chances do we have of enumerating every species and tallying them up?

Bambusa vulgaris

The genus Bambusa includes about 150 species, not including dozens of cultivars, making it one of the most extensive. And Bambua vulgaris is almost certainly the most widespread species of all.

The name means “common bamboo“, and this species of Chinese origin now grows all over the tropical world, thanks to the ambitious explorers and the scientific seafarers of the 18th and 19th centuries. With such a long history and wide geographic distribution, it’s not surprising to see Bambusa vulgaris producing a divergent array of offspring.

It’s well known that there is yellow vulgaris all over Latin America, and that the yellow and green vulgaris have both proliferated across Africa. But authors have yet to redefine these variants as separate species. Certain striped varieties of vulgaris, on the other hand, have earned recognition as a subspecies, usually referred to as ‘Vittata’ or Painted Bamboo.

Vulgaris most likely originated in China. But farmers and ethnobotanists of northeast India may argue otherwise. This region, around the state of Assam, is teeming with native bamboo populations of all kinds.

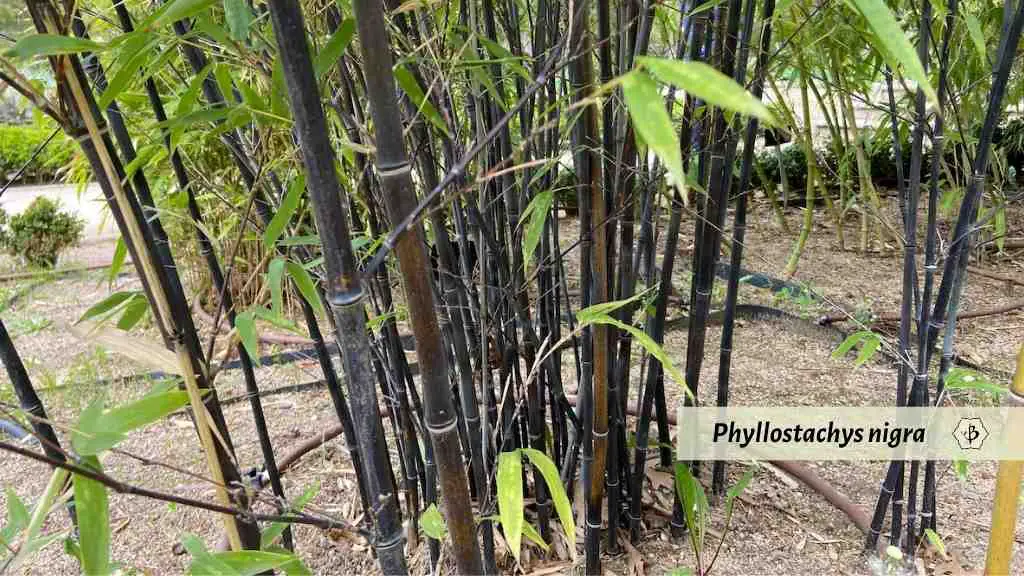

Phyllostachys nigra

The genus Phyllostachys is made up of all sorts of running bamboos, about 50 species in all, plus a panoply of subspecies. They are some of the most vigorous and fast-spreading of all bamboo. This can be a point of concern for many growers, but it has made them extremely successful and prolific.

Black bamboo, Phyllostachys nigra, is one of the most popular species of decorative bamboo, thanks to the striking, shiny black color of its slender culms. Who would guess that giant Henon bamboo, with culms over 50 feet tall and 4 inches thick would be a cultivar of this ebony ornamental?

Henon is a subspecies of Black Bamboo, but with grayish-green culms. It also goes by the common name Giant Gray Bamboo. It’s one of the best timber bamboo species to grow in North America. It’s hardy, fast-growing, and has thicker walls than most other Phyllostachys, making it more suitable for building and light construction.

Some other interesting Phyllostachys are the striped cultivars. P. aureosulcata ‘Spectabilis’ and P. aura ‘Aureocaulis’ are especially eye-catching. Their striping is similar, but ‘Spectabilis’ sometimes grows with an exotic zigzag. Again, these varieties are distinct in appearance, but not deemed worthy of speciation.

Adding more bamboo species to the count

As you can see, defining and identifying bamboo species can be quite difficult. So, arriving at a definitive number of how many bamboo species there are, is next to impossible.

As soon as you have a complete list, it’s inevitable that some researcher, deep in the jungles of Brazil or Myanmar, will surface with a great new discovery. The equatorial tropics have the most suitable conditions for most species of bamboo. It’s also where plant life proliferates most quickly, increasing the likelihood of hybridization and occurrences of speciation.

Such discoveries are not at all uncommon. Belen Fadrique, a Spanish researcher working in the Amazon, found several new species of bamboo, as described in a 2022 field guide. And in the spring of 2025, Natalia Reategui and her colleagues identified and published a new species from the genus Aulonemia in the Andes. Truly, the latest number of bamboo species is anything but complete, and it’s only a matter of time before new varieties appear.

And that’s only accounting for natural variation. Humans, meanwhile, are also hard at work breeding and crossbreeding strains and developing new bamboo hybrids. Bamboo gene editing is also underway. And as interest in bamboo farming grows and spreads to new territories, these practices are only going to increase.

So, for the time being, let’s all just agree that the number of bamboo species is huge. At this point, more than 1,600 distinct species have been identified, with another few hundred cultivars generally accepted by the scientific community.

Further reading

If you enjoyed learning a little bit about bamboo species and classification, you won’t want to miss these other in-depth articles about the wondrous diversity of bamboo.